The city’s landmark Right to Counsel law was the country’s first to guarantee legal representation in housing court to low-income tenants most at risk for eviction. But advocates and providers say it’s been undermined in recent months as the courts schedule eviction cases faster than there are available attorneys to take them. “When the law was first passed, it worked,” Ruth Riddick, a Flatbush tenant, testified Friday at a city hearing on the initiative.

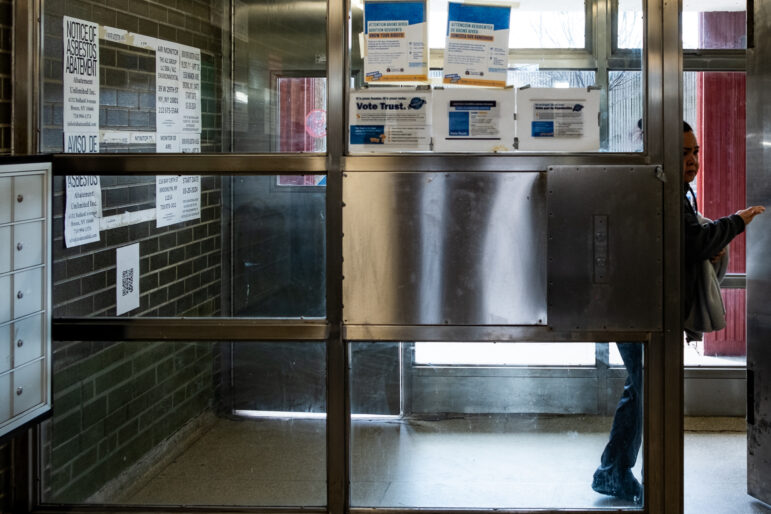

Annie Iezzi

Ruth Riddick, a Flatbush tenant and member of the Right to Counsel Coalition, at an in-person broadcast of the city’s hearing on the program Friday.The last way most New Yorkers want to spend a Friday night is attending a public hearing on Zoom. But last week, more than 150 tenants, advocates, lawyers, landlords and elected officials tuned into the hearing on “Universal Access to Counsel” hosted by the Office of Civil Justice.

In January, City Limits reported that the OCJ did not host a public hearing in 2022, even though the legislation that established the program, also known as Right to Counsel, mandates it hold at least one hearing a year. The lapse was especially egregious during a time when the number of tenants heading to housing court with the help of an attorney has dropped steeply—the result, advocates say, of a court system scheduling eviction cases faster than there are available housing attorneys to take them.

The Friday night hearing felt to some like a similar snub.

“Despite the hearing being designed to discourage participation, RTC is too important,” wrote the Right to Counsel NYC Coalition in its media advisory for the event. The Coalition, which pushed for Right to Counsel to become law, hosted an in-person broadcast of the hearing at its offices in SOHO, where members offered group testimony over Zoom.

New York City’s Right to Counsel law was the country’s first to guarantee representation in housing court to the tenants most at risk for eviction: those within 200 percent of the federal poverty line. Before the law went into effect in 2017, just 1 percent of tenants facing eviction in New York City had a lawyer—something experts say greatly increases someone’s chances of remaining in their home—according to estimates by NYU’s Furman Center.

More recent numbers cited by the NYC Eviction Crisis Monitor, an online tracking tool created by the housing advocacy groups Association for Neighborhood Housing and Development (ANHD) and other members of the Housing Data Coalition, show that the number of city tenants facing eviction taken to court in January 2022 who had a lawyer climbed to 66 percent, regardless of income (it should be noted that the Monitor and Furman Center used different methodologies in their calculations).*

But the number of represented tenants has dropped since the state’s COVID eviction moratorium was lifted at the start of last year, dipping as low as 27 percent for tenants that were taken to court in November 2022, the Monitor tool shows. The current rate of representation for all cases filed since the state’s eviction moratorium ended on Jan. 15, 2022, is 47 percent, according to Lucy Block, a senior research and data associate at ANHD. She estimates that the majority of those tenants—82 percent—would qualify for a lawyer through Right to Counsel.

“When the law was first passed, it worked,” testified Ruth Riddick, a Flatbush tenant and member of the Right to Counsel Coalition. “However, today, Judge Cannataro is not mandating the courts to slow down the cases. Many tenants are already intimidated just being in court, and they often do not know their legal rights.”

In a statement, the Office of Court Administration said it has already made an effort to adjust its schedules to accommodate RTC cases. “The New York City Housing Court has for a long time now adjusted its calendars to afford tenants opportunities to meet with legal service providers and [adjourned] the cases for legal service providers to assess cases,” wrote Lucian Chalfen, public information director for the OCA.

In his 2023 State of Our Judiciary Address, Acting Chief Judge Cannataro said that New York courts “are conscientiously endeavoring to maximize efficiencies and shift resources to … keep our dockets moving swiftly.” He added that, “many courts around the state have undertaken measures to facilitate increased access to self-help resources and legal representation in housing disputes.”

The city has disputed the numbers tallied by the Crisis Monitor tool, saying it uses state eviction data that doesn’t differentiate for cases that are inactive, resolved outside of court or where tenants are provided with brief legal advice instead of full representation in court. In a statement, the city’s Department of Social Services (DSS), which oversees the OCJ, also defended the scheduling of Friday’s hearing.

“As is standard with public hearings of this nature and/or Community Board and any such community meetings in NYC which are scheduled after business hours to be mindful of community members’/advocates’/stakeholders’ availability, the remote hearing was scheduled at a time that would encourage the widest participation possible,” a spokesperson wrote.

Calendaring and contracts

“The NYC Right to Counsel coalition has been calling on the courts to slow down the pace of new eviction cases to allow legal service providers time to provide meaningful representation,” testified Addrana Montgomery, a staff attorney on the Housing Rights team at TakeRoot Justice.

According to Montgomery, on the most recent intake day that TakeRoot Justice staffed in Queens, more than 100 new cases were calendared for the eight housing attorneys at TakeRoot. Often, lawyers are able to spend just minutes with each new client. “The quality of representation that each of my clients deserve is not compatible with the court’s demand for speed,” said Montgomery.

TakeRoot contracts with the city to provide legal support for groups of tenants fighting harassment and did not bid on a Right to Counsel contract, but it is providing RTC services anyway. According to Keriann Pauls, a co-director of TakeRoot’s resource management team, the terms of their most recent legal services contract were changed by the city from previous years. Instead of an option to accept referred Right to Counsel cases, she says that TakeRoot is now obligated to do so, or risk losing out on over $1.5 million in funding.

That means fewer resources for the nonprofit to do other kinds of tenant advocacy work, Pauls said.

“But what do we do?” she asked. “To walk away from the City contract when there’s currently no one else who will cover this funding means that organizations like ours cannot serve our communities in a way that fits our mission and model. So you feel stuck.”

The Office of Civil Justice, in response to a FOIL submitted by City Limits, provided 30 of its current Right to Counsel contracts, including a breakdown of the money paid to each organization, with the bulk of funding allocated to personnel services, including paying for attorneys, paralegals, and caseworkers.

The contracts are structured to pay legal service providers for “units of service.” Legal representation in court counts as one unit, and “brief legal advice” is counted as one-third of a unit. For example, the Neighborhood Association for Intercultural Affairs in the Bronx has a $13 million contract that requires it provide 5,362 units of service this fiscal year, while a smaller organization, the CAMBA Staten Island Extension, is obligated to provide 406 units as part of its $982,229 contract.

In an email response to City Limits, a DSS spokesperson said the city has “significantly increased investments in tenant legal services” from $166 million in Fiscal Year 2021 to more than $200 million in FY2022.

The OCA had previously cited, “the inability of the Right To Counsel providers to staff intake calendars” as “the real reason” eligible tenants aren’t receiving representation. But all Right to Counsel providers received a rating of “good” or “excellent” in every annual OCJ performance review from 2017-2021, with one exception in 2017. City Limits is awaiting a FOIL response for the 2022 performance reviews.

Annie Iezzi

Brenda Lott, a member of the Right to Counsel Coalition, wearing a shirt in support of the program.

Not enough attorneys

In addition to the speed of court cases, stakeholders say there also aren’t enough lawyers doing the pro-bono RTC work to meet demand.

“Providers want to help every person that we’ve spoken to,” said Austen Refuerzo, supervising attorney at the Neighborhood Defender Service of Harlem. “The numbers just don’t work without more attorneys.”

The rate of housing attorney attrition in Fiscal Year 2022 was 37 percent across legal service providers participating in Right to Counsel, according to Kristie Ortiz-Lam, the director of the Preserving Affordable Housing Program at Brooklyn Legal Services Corp A, which lost 10 staff attorneys in 2022.

“There are currently 65 vacancies across providers with the number of vacancies increasing every day,” testified Ortiz-Lam. Data gathered from 14 of the major Right to Counsel legal service providers show that there are only 489 housing attorneys available to represent tenants who are eligible, she added.

“We are faced with eviction and no lawyer is in sight to assist,” testified a tenant at the public hearing. “No one in the courtroom explains that we have a right to free legal services, not directs us to where we could get those services. We’re alone, no lawyer, no assistance, and the discussion in the mediator’s room generally favors the landlord.”

Officials confirmed that the city is working on adding to its roster of contracted providers.

“We are in the process of issuing a new solicitation for RFPs in the coming months, inviting existing and new legal service providers to partner with us on the continued and effective citywide implementation of RTC,” wrote a spokesperson from the DSS in response to City Limits.

The city has also issued a Request for Expression of Interest “to identify additional legal service providers to supplement existing program capacity” the spokesperson added. “As part of this effort, we are already in the process of procuring an additional legal services provider.”

The growing burden on Right to Counsel attorneys reflects broader issues across the legal services landscape. Last week, more than 150 attorneys from RTC provider NYLAG went on strike, citing organization-wide issues with caseloads, healthcare and pay.

“People are leaving and then [as a result] institutional knowledge is leaving the organization,” said Simone Meyer, a senior staff attorney with NYLAG and co-chair of external communications for the union leading the strike, ABN. “Because there’s not enough funding, then you’re not getting to hire more people, or you’re getting new young attorneys. In a lot of ways that means you have to start from scratch.”

In a statement, a NYLAG spokesperson said the organization recognizes its workers’ concerns, but that it is limited in its ability to address them in lieu of higher-paying government contracts.

“Like many nonprofit legal services organizations in New York City, the vast majority of NYLAG’s funding comes from government contracts. As such, NYLAG is constrained in the degree to which we can increase employees’ compensation with contracts that do not meet rising costs, while also ensuring our organization’s long-term fiscal health,” a rep for the provider said.

“NYLAG is committed to pushing for change to address the systemic root causes of our funding constraints by advocating for contracts that enable us to increase wages, benefits, and support for staff.”

‘A legacy-defining moment’

Small landlords also feel that Right to Counsel is underfunded, arguing the law privileges both large landlords and tenants over families that own property in New York City. Those small landlords should also be entitled to free housing court representation, said Ann Korchak, board president of Small Property Owners of New York.

“I would say that the Right to Counsel should apply with means testing to both the tenant and the building owner,” she said, saying small property owners often lack the funding and resources to navigate court cases on their own compared to bigger corporate owners.

“Our experience in housing court cannot at all be compared to a large institutional owner’s experience in housing court. They often have internal staff or relationships with large law firms who handle their cases,” she said.

Most New Yorkers live in apartments owned by large landlords. In 2018, just 13 percent of housing units in the city were owned by landlords with less than one building, according to the housing nonprofit JustFix. Landlords that have two-to-five buildings own 15 percent of housing units, while “large landlords” that have portfolios of 21-60 buildings and “very large landlords” of 61 or more buildings own 52 percent of apartments across the five boroughs.

City Limits attempted to reach 20 of the city’s largest landlords—some of which own tens of thousands of apartments—to get their comment on Right to Counsel, though the companies did not respond to multiple requests for comment. NYCHA, which has more than 175,000 apartments across the city, acknowledged City Limits’ requests but did not comment on Right to Counsel, referring questions to DSS instead.

The New York City Council’s Committee on General Welfare pushed back a follow-up oversight hearing on the program initially scheduled for this Friday that will now take place on March 27 at 10 a.m.

Advocates and progressive lawmakers say it’s essential the city address the issues undermining the success of Right to Counsel, at a time when eviction cases are on the rise and the city’s homeless shelter population has ballooned to historic highs.

Bronx Borough President Vanessa Gibson, who testified at Friday evening’s hearing, wrote in an email to City Limits that she is concerned about insufficient funding. “I urge the city to fully support the RTC Coalition’s request for an additional $70 million to ensure that all New Yorkers have their rights respected in Housing Court.”

District 7 Councilmember Shaun Abreu, a former tenant lawyer who was himself previously evicted, remains optimistic that the promise of Right to Counsel can be fulfilled. His office recently sponsored two legislative items related to improving the initiative: including a resolution calling on state lawmakers and the governor to pass legislation requiring the court system to slow the pace of eviction cases, and Introduction 921 to pay legal service attorneys at parity with attorneys working for the City Law Department.

“This is a legacy-defining moment for the city to stand up and say we’re going to fight to protect this program that is keeping so many of our families in their homes,” said Abreu. “If the city does not stand up to save Right to Counsel as we know it can be, that will be a sign of failed leadership. And I’m confident that the city will not take this route.”

*Editor’s note: This story was updated after publication to clarify some of the numbers cited from the NYC Eviction Monitor Tool, which refers to cases in New York City alone, not statewide as previously stated. The 47 percent number is the rate of representation for all cases filed since Jan. 15, 2022.

2 thoughts on “At Overdue Hearing, Advocates Push NYC to Fulfill Promise of Housing Court Help for Low-Income Tenants”

Here on the same day we have housing legal support issues with respect to tenants (Right to Counsel) and homeowners (foreclosure defense).

If these are to happen they can be handled by the same attorneys, statewide, state funded. They should set up an independent administrative body and the lawyers work for that body, just one body, not a patchwork of nonprofits competing with one another in clawing for state funds. Hire lawyers not firms

Hi my name is monea Powell and I have been living in a shelter for 3 years looking for a one bedroom apartment I have city feps every time I try to call a leasing agent they are not not calling me back or not wanting to accept my city feps voucher