The City Has Two Opportunities to Advance Community Led Plans, Will They Take Them?

The Bushwick and Chinatown/Two Bridges Plans Offer a Chance to Flip the Script

Land use issues have been in the news constantly in recent years – from the de Blasio administration’s neighborhood rezonings, to the failed Amazon H2Q proposal, to mega-developments like Hudson Yards. This increased attention on how our land is used comes hand-and-hand with a growing understanding among community groups and residents, in all five boroughs, about the vital role land use decisions play in determining the future of our neighborhoods and our city at large.

But how is land use planning actually done in New York City? Who has real decision-making power in the process? And what happens when historically marginalized communities put forward their own visions for land use in their neighborhoods? The outcome of a pair of community plans in two different neighborhoods – Bushwick and Chinatown/Two Bridges – will go a long way towards providing some answers and determining the current state of community planning in New York City.

Zoning and Land Use Planning

Land use planning involves more than just zoning – it includes capital investments for necessary infrastructure and amenities, money for city services, and policies to promote goals like equitable economic development and anti-displacement. But zoning is the fundamental tool determining what our neighborhoods look like and, in large part, how they function. It’s why some neighborhoods have a proliferation of high rises or office towers, why some neighborhoods are mostly 4-story rowhouses, or why some neighborhoods that are mostly 4-story rowhouses can see new development that’s significantly taller (like a 12-story building rising in the middle of a 4-story block). A neighborhood’s zoning matters, and no land use plan can be complete if it isn’t considered.

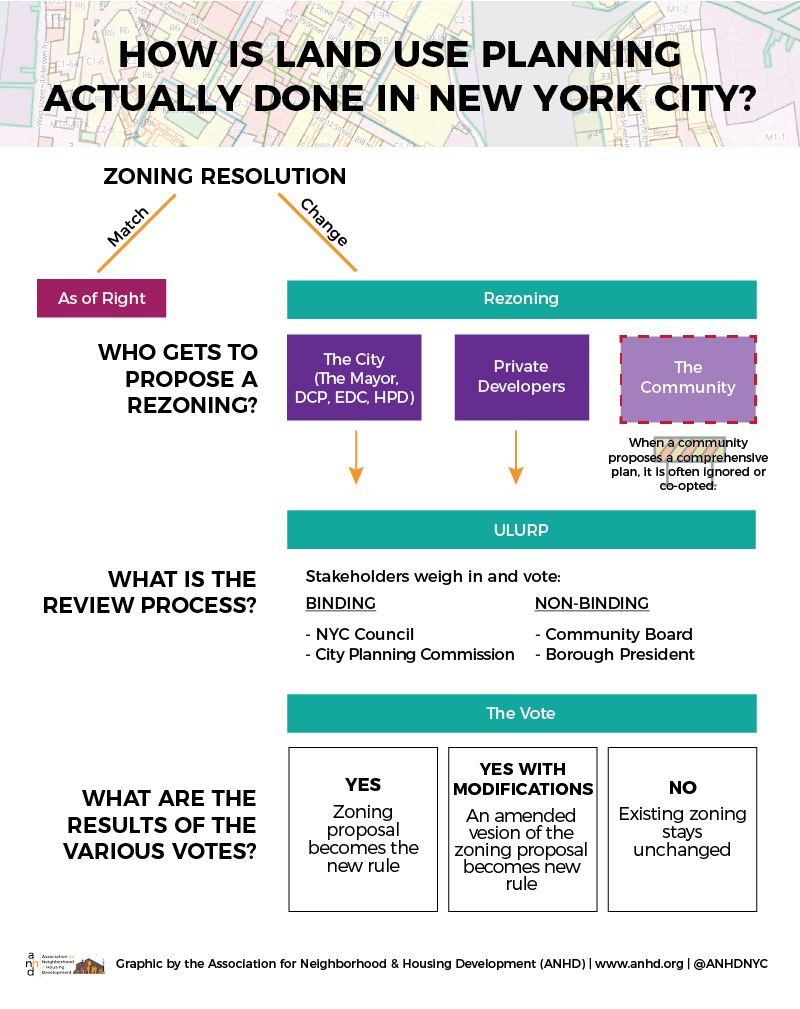

The current Zoning Resolution was written in 1961, but it is constantly being changed through zoning text and map amendments. When a developer wants to build something that is allowed by the existing zoning, this is called “as-of-right” development and it can happen without public review. However, if someone wants to change what the zoning resolution currently allows– either across a few lots or in a wide-swath of a neighborhood – they must go through the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP), requiring the approval of both the City Planning Commission (CPC) and the City Council.

Who Gets to Propose Zoning Changes?

Who gets to propose these changes to existing zoning? First and foremost is the City, primarily the Mayor’s Office through the City Planning Commission and other agencies (Department of City Planning or DCP, NYC Economic Development Corporation or EDC, Housing Preservation & Development or HPD). But officially any resident (“taxpayer”) or group can apply for changes in the zoning resolution. And in fact, the zoning resolution is changed all the time by such “private applications,” as developers bring specific projects before the City. Though City-proposed rezonings tend to encompass larger land areas, at any given time most rezoning applications being considered by the City are private applications. Most often these are developers looking to build something larger or more permissive than the zoning currently allows, with the money and technical capacity to take their projects through the expensive and time-consuming environmental review process that accompanies ULURP. The Department of City Planning will work with them to craft a proposal that fits a public purpose and so can justify the zoning change (officially they can’t just say, we want to make more money with a bigger building).

Changing the zoning in a neighborhood, even for specific developments, means changing the amount of development that can take place and has significant ramifications for the community. So where is the role for local community members? The City argues that’s what ULURP is for: the chance for the public to give their feedback and, through the local Council Member, to negotiate desired changes. But ULURP is by its very nature reactive; where there is conflict between the proposal and a community’s priorities, they are left to either accept projects they don’t like in exchange for needed public benefits or to say no outright and be accused of being anti-development or against change. (FIGURE A – ULURP & The Vote)

Communities Get Left Out

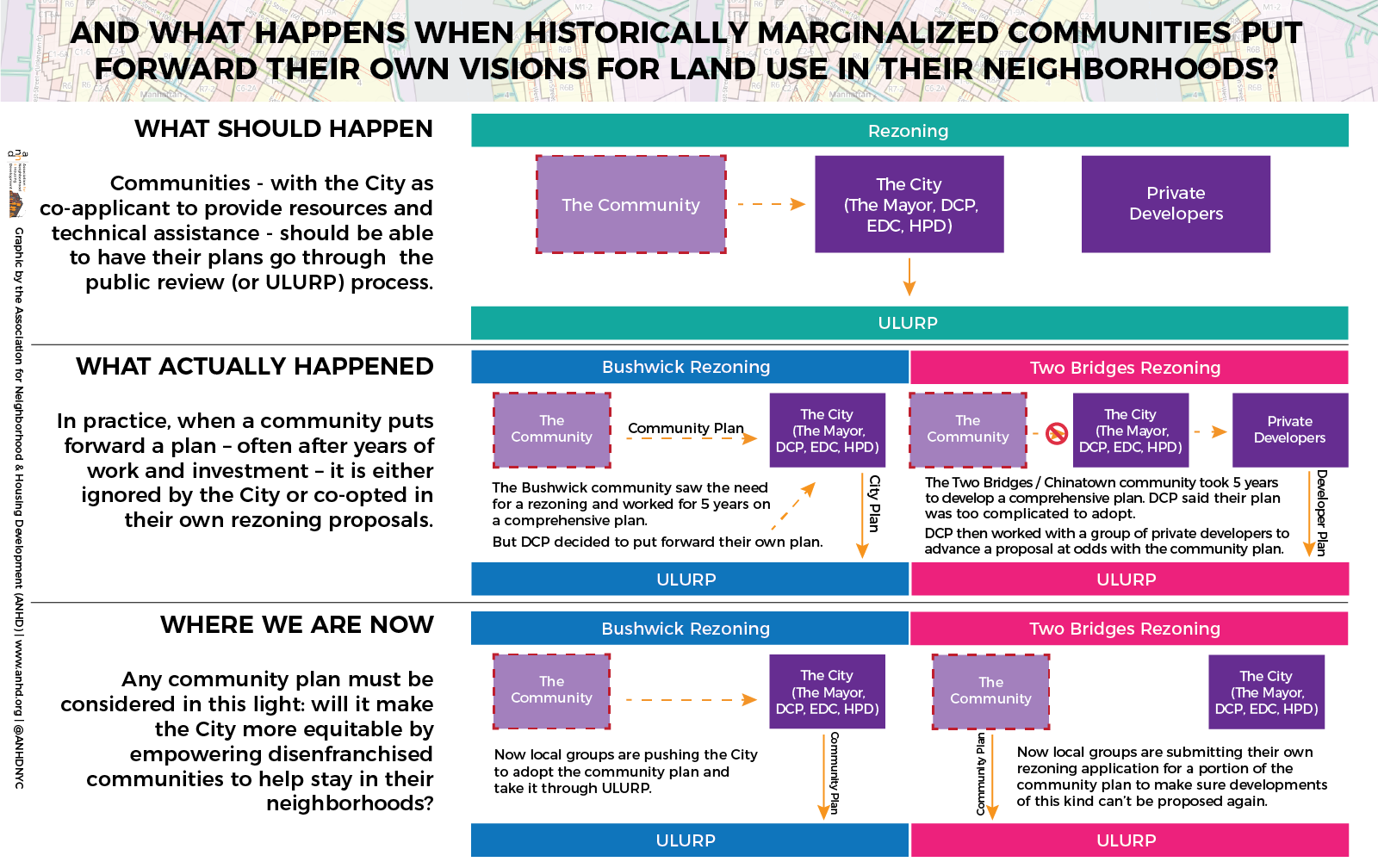

When communities try to break out of this dynamic and put forward their own proactive visions for development and the future of their neighborhoods, they are rarely taken seriously. In practice, when a community puts forward a plan – often after years of work and investment – it is either ignored by the City or co-opted in their own rezoning proposals, as was the case with both the Bushwick Community and the Chinatown Working Group plans. (FIGURE B – WHAT ACTUALLY HAPPENED) Without the City’s support and willingness to sign on as co-applicants, it is often too expensive and time-consuming for communities to advance these plans on their own, especially the larger and more comprehensive they are. With communities constrained in this fashion, deciding where and how neighborhoods should change is essentially left to the mayoral administration and private developers. Communities are left to weigh in on and attempt to influence others’ proposals, rather than initiate their own positive, holistic visions for their neighborhoods; they are relegated to a reactive, rather than proactive role.

Fortunately, the City has not just one but two opportunities to flip the script here and move forward community-created plans in two different neighborhoods: Bushwick and Chinatown/Two Bridges. Though the specific details vary, the idea is the same: these are plans that came out of years of work by local residents and stakeholders in order to address existing and anticipated future needs in their communities, prompted by existing zoning and development that isn’t benefitting the neighborhood, and in fact is actively harming its long-time residents. These are proactive plans to better channel and control neighborhood growth, minimize the negative impacts of luxury development, and address needs for affordable housing, community space, local businesses, and more – working in tandem with other policies and investments to help ensure that these historically low- and moderate-income communities of color remain affordable and inclusive for all. This is the most important thread tying them together. Any community plan must be considered in this light: will it make the City more equitable by empowering disenfranchised communities to help stay in their neighborhoods? For both the Bushwick and Chinatown/Two Bridges plans the answer is yes.

The approach local groups are taking in these neighborhoods vary. In Bushwick local groups, residents and electeds are pushing the City to advance the community plan through ULURP, or at the very least consider it as an alternative to the plan the City put forward. In Chinatown/Two Bridges, local groups have submitted their own rezoning application as a first step in ensuring the Chinatown Working Group plan gets passed in full. (FIGURE B – WHERE WE ARE NOW) But regardless of the approach, the ultimate question remains the same: will the City respect these local communities’ efforts to take the driver’s seat in their own neighborhoods and help to advance these plans to ULURP as proposed? The answer will go a long way towards determining who has a real say in the future of our neighborhoods and our city.