Low-Income and BIPOC Communities Need More Access to Banking, Not Less

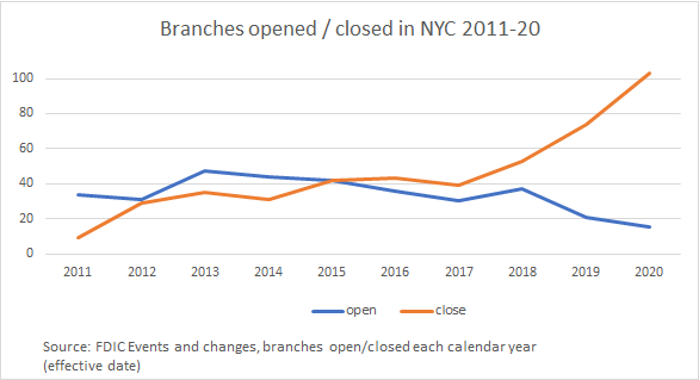

Branch closures have been on the rise for the last decade and accelerating in recent years nationwide. A similar trend is present here in New York City. From 2011 to 2020, the number of branch closures in the City has increased as openings declined nearly every year.

This pace of Bank closures accelerated rapidly in 2019 and into 2020 when COVID hit. Over 100 branches closed in 2020 in New York City, up from 74 in 2019 and 53 in 2018. While many of the closures and openings were in higher-income and well-banked areas (i.e., lower Manhattan), over a quarter (27) of these bank closures were in low- and moderate-income census tracts, and 20% (21) were in majority Black or Latinx census tracts. The closures are continuing into 2021.

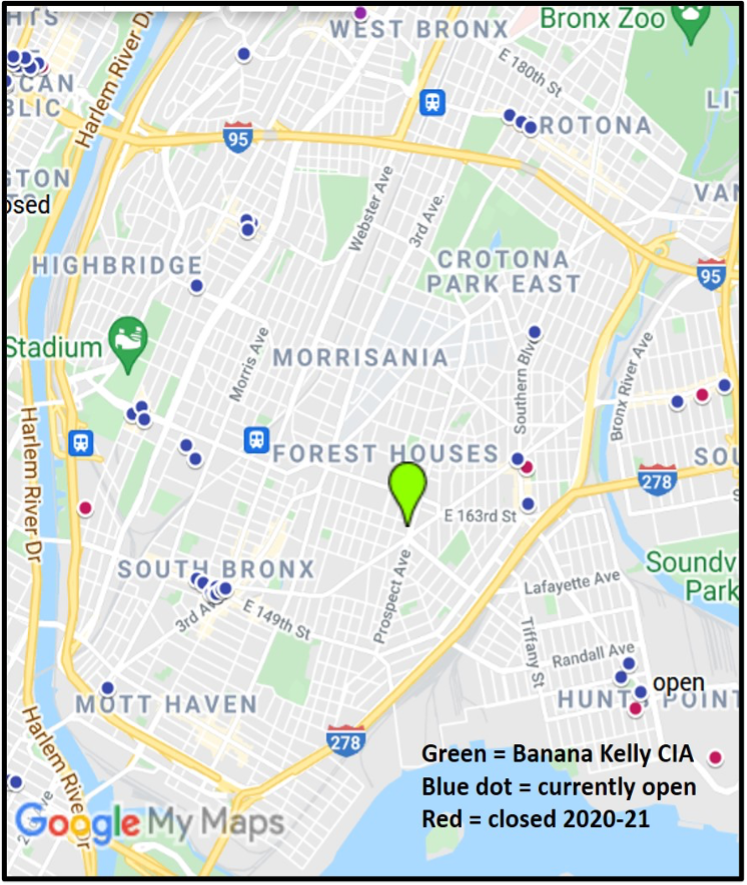

Click here to view the map in a new browser window.

The rise in online banking and bank mergers and consolidations are two factors that contribute to this trend, with the former being the one most cited by banks. While this may be true, it does not justify closing branches in historically redlined BIPOC, immigrant, and LMI communities where residents have long been locked out of traditional financial institutions. Bank closures in these communities further exacerbate inequities for residents and workers of that community, leaving them without sufficient access to banks and affordable, accessible products, especially when they so often lacked this access before the closures.

Take the Bronx, which has the highest rates of unbanked and underbanked households, the lowest concentration of bank branches per household, the highest percentages of Black and Latinx residents, and the poorest residents in the city. The Bronx also has the highest concentration of alternative financial services (AFS) to branches, such as check cashers, non-bank ATMs, and other non-bank services that can carry high fees per transaction. In the Bronx, seven banks collectively closed 17 branches from 2018 to 2021 - and, over half were in 2020 - reducing the total number of full-service branches to just 131, down from 144 in June 2018. This represents a 9% drop in a borough with nearly 1.5 million people.

closed since 2020 in Sonya's neighborhood.

Sonya Ferguson, a leader at ANHD member organization Banana Kelly Community Improvement Association, understands this issue personally. Sonya serves as the president of the Block Association on Kelly Street in the South Bronx, a block made famous in the 1970s when longtime residents took over abandoned buildings and used sweat equity to create community-owned housing. Sonya laments the impact of the lack of bank branches in the area. She knows all too well that while some folks make the long hike to the singular bank branch on Southern Boulevard or a larger cluster in the further-away Hub at Third Ave and E. 149th Street, many on the block rely on local check cashers, pawnshops, and bodegas to handle their financial transactions.

“Like many in my neighborhood, my income from disability and the new stimulus goes to a debit card called DirectExpress,” says Sonya. “I try to find the ATM with the lowest fees, but sometimes you are desperate and have to pay $2 to get your money. I also have to pay additional fees to pay my bills, such as rent, Con Edison, phone bills, etc.”

For the many families who rely on disability payments in the area, these ubiquitous small fees add up quickly. New Yorkers without the DirectExpress card or a bank account will face additional hurdles and fees to access their stimulus and tax refunds, either by check or prepaid debit card. Further, people who mainly deal in cash must conduct business in person -- during a pandemic -- and by mail to purchase money orders and pay bills. Sonya described waiting in long lines to handle these transactions at a check casher or at the one nearby bank, a tiny Chase branch on Southern Boulevard and Westchester Avenue where the lines often stretch around the corner. Even people who may want to use online banking alone, or in conjunction with a branch, need access to the internet to do so, yet 18.6% of Bronx residents lack access to the internet, and that jumps to over 30% for families earning below $20,000.

Bank closures across New York City disproportionately harm Black and Latinx communities -- the people who live and work there, the institutions that serve there, and the small businesses that operate and create jobs there. For this reason, community groups are speaking up. Last year, groups protested against Amalgamated Bank for closing their publicly-subsidized Banking Development District branch on Burnside Ave in the West Bronx. Groups have also called on Chase to swiftly reopen their Burnside Ave branch after being closed for a year. These closures left thousands of residents and businesses without any commercial bank branch in their neighborhood. Added to this list are Popular Bank and Sterling Bank who both recently closed branches in the South Bronx. The Popular closure was on Southern Boulevard, not too far from where Sonya lives and where roughly 30% of residents do not have a bank account.

Time and again, banks close without any repercussions or requirements to serve the communities they leave. In fact, banks do not even have to apply to close: they simply notify their federal and state regulators. At the federal level, banks are regulated by either the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), or the Federal Reserve Board. New York State chartered banks are also regulated by the NY State Department of Financial Services.

In some cases, public comments may lead to convenings to discuss the situation, but in the end, banks usually are still allowed to close without making up for the loss to the community. For example, state regulators determined the Popular branch closure “will not result in a significant reduction of banking services in the communities to be affected,” and so it closed. This process is flawed, especially as we consider it next to Sonya’s story and how the acceleration of closures affects her wallet and economic precarity.

ANHD’s Equitable Reinvestment Coalition (ERC) is a member-led coalition that believes racial and economic justice and equity must be central to our financial system, and ERC has been growing in numbers to address this public equity crisis. ERC is dedicated to holding financial institutions accountable for the wealth and racial inequities they helped create and continue to perpetuate through practices and policies of wealth extraction, exploitation, and displacement.

ERC is calling for an immediate halt to branch closures in BIPOC and low- and moderate-income communities until the economic crisis passes. Further, there must be a better process in place to ensure the community has equitable access to banks and affordable, accessible bank products before banks can close branches in BIPOC or LMI neighborhoods.

The coalition understands this is not an easy feat, and creative solutions are needed. For example, bank regulators could create a process to evaluate a bank’s efforts to serve the BIPOC and LMI communitie they are in. They can assess additional steps the bank can take to reach unbanked and underbanked populations better. In the rare cases where there are sufficient branches, they could evaluate a bank's plan to expand banking to other underbanked communities while maintaining a presence through other reinvestment activities. Banks could also elect to do this evaluation and assessment on their own accord.

The coalition is dismayed that government bank regulators charged with enforcing the Community Reinvestment Act do not currently have the authority to ensure and maintain equitable bank access for all. Still, they should use all the power they have to support these goals and improve the system. ERC is ready to work with regulators and other stakeholders to ensure LMI and BIPOC communities have equitable access to bank branches and banking.

Despite decades of organizing to pass, strengthen, and enforce the Community Reinvestment Act, redlining and related forms of systemic racism persist in our neighborhoods. Access to a physical bank branch is the first point of entry for many to conduct day-to-day transactions, build credit, and ultimately access affordable products that allow people to build wealth through savings, homeownership, and entrepreneurship. Every time a branch closes in a historically redlined neighborhood, we move further away from our goal to build and keep wealth in our BIPOC and low-income communities. Let’s make it easier to open a new branch than to close one down, and you can take that to the bank.