How Our Planning Priorities Got Us to COVID-19 Disparate Impacts

By now the disparate impact of COVID-19 has been well documented. As early analysis by ANHD has shown, the virus has hit low-income communities of color at a staggering rate; Black and Latinx New Yorkers are dying of COVID at twice the rate of white residents. Though these disparities are true across the country where nation-wide, Black Americans are dying from COVID at nearly three times the rate of whites, New York City has had the most COVID cases and deaths of anywhere in the United States. In response, a line of thinking has emerged from pundits to politicians that seems to say this is expected and inevitable: as the largest and densest city in the country – New York – was bound to be the hardest hit.

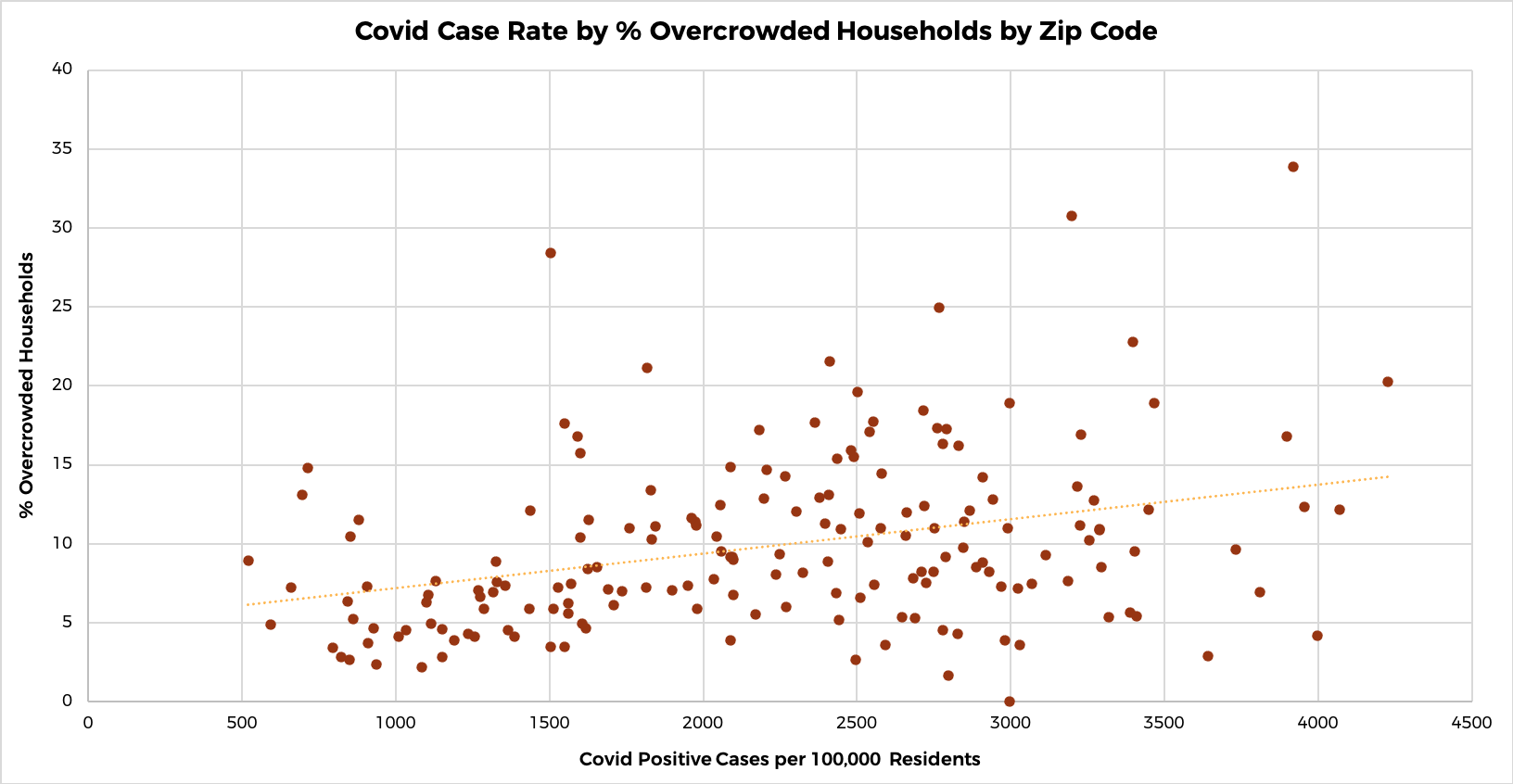

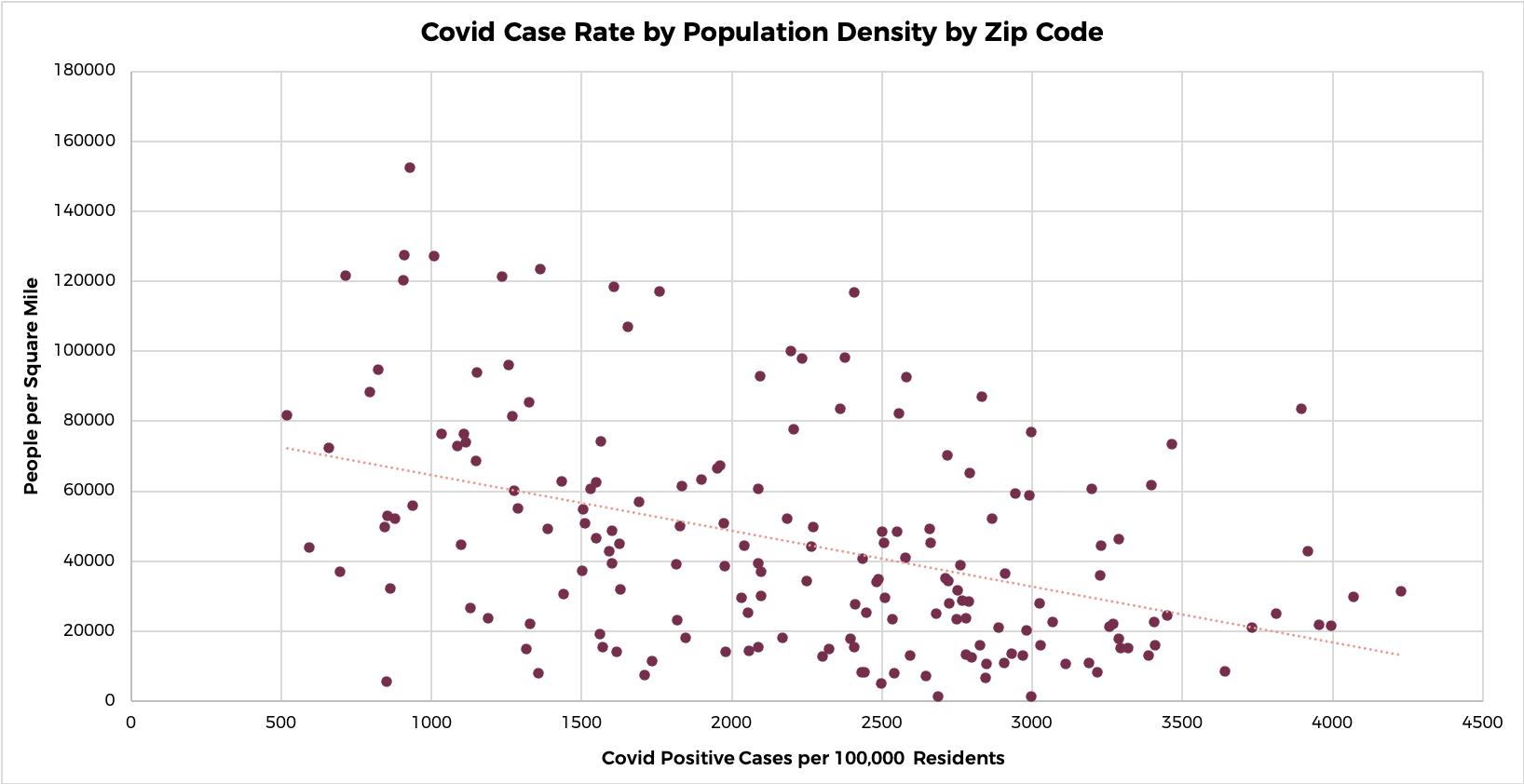

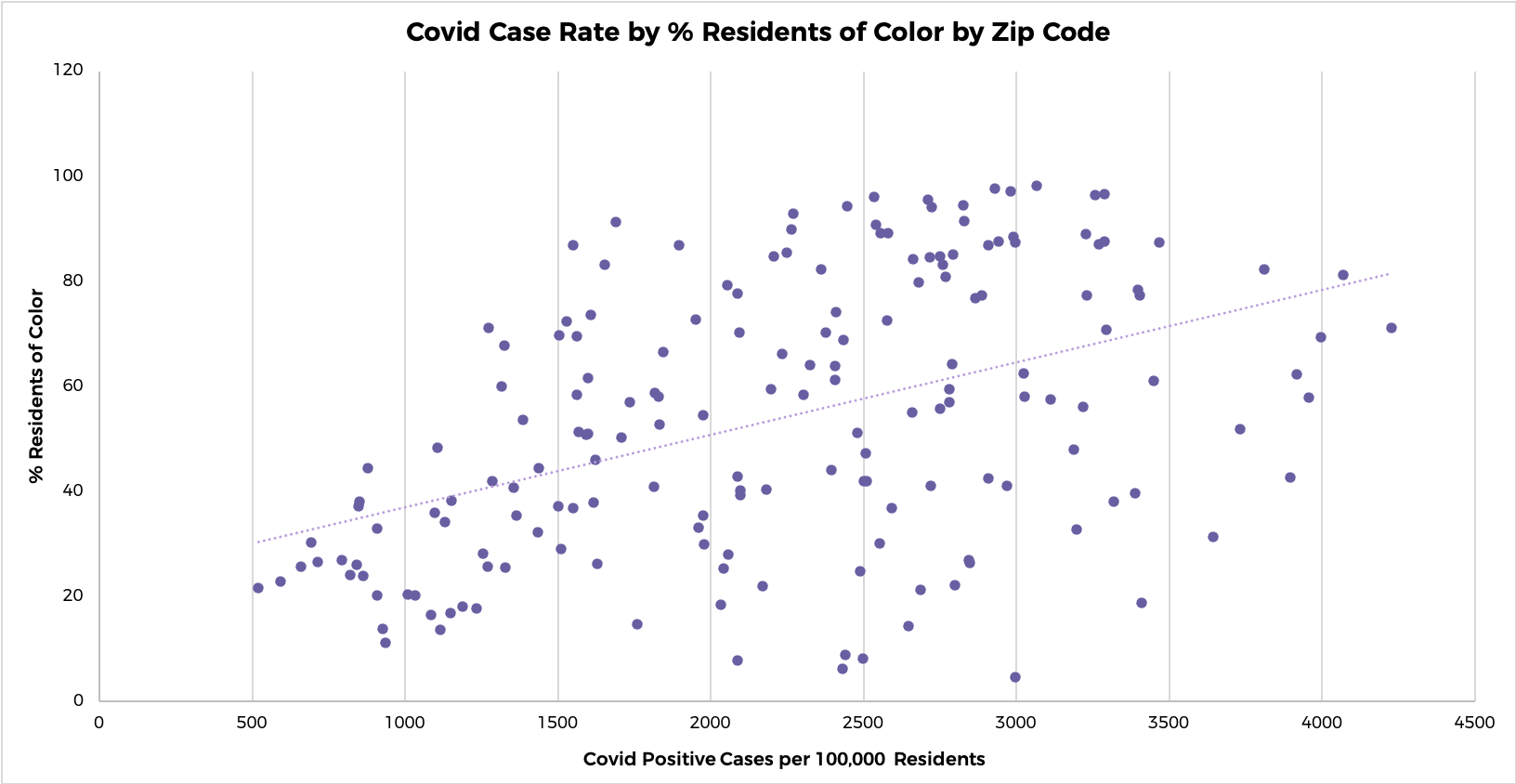

This theory ignores the geography of disparate impact within New York City and the reality, as the New York Times and the NYU Furman Center have pointed out, that density alone has little correlation with the impacts of COVID. In fact, when looking at density and COVID cases by zip code, the trend clearly moves in the opposite direction: the denser a neighborhood in general, the lower the case load. Correlation with high rates of COVID is apparent in overcrowded households in communities of color – a metric that directly reflects the history of segregation and inequity in our city. Whether a neighborhood is dense or not doesn’t matter in terms of the impacts of COVID. What matters most is whether it is a neighborhood where households of color live, especially if those households are overcrowded. This is to say, it isn’t our densely populated city that’s responsible for COVID’s heavy and disparate impact on New York – it’s our segregated and inequitable city that bears the blame.

This geography of inequity didn’t just happen by chance. Rather, it is the predictable outcome of decades of planning decisions that favored the interests of whiter, wealthier New Yorkers above all others. While recent battles have centered on zoning, planning includes not only land use and development choices, but decisions about policies, programs, and capital investments. It is a reflection and indication of what and – just as crucially where – is being prioritized: from affordable housing to transit improvements, public hospitals to parks and open space. It is the underlying assumptions that dictate why certain communities are told time and again that their needs are impossible to meet, while other communities’ desires go mostly unquestioned. The ramifications of the City’s approach to planning can be seen across a host of metrics today, from access to healthcare and healthy food to good paying jobs, from accessible and well-cared for open space to overcrowded housing conditions.

Overcrowding is but one manifestation of this approach, but its correlation to the impact of COVID, especially as compared to the impact of density, is a prime example of the failures of planning – one that reflects our priorities as a city and who we choose to serve. Overcrowding and density are not the same thing. Density refers to how many people occupy a piece of land, whereas overcrowding refers to how many people occupy an apartment – how many homes are in a neighborhood versus how many people live within them. The Upper East Side of Manhattan, for example, is one of the most densely populated neighborhoods in the city, but one of the least overcrowded: its residents generally live in big apartment buildings, but with larger apartments with more space and fewer people within them. Corona, Queens, on the other hand, is almost a third as densely populated as the Upper East Side, yet over a third of its residents live in overcrowded housing, meaning larger households sharing smaller apartments. The Upper East Side as a neighborhood has been mostly spared from the impacts of COVID; Corona has been one of the hardest hit.

Overcrowding is a direct legacy of our history of segregation. It is the outcome of restricting, through a wide variety of explicit and veiled policies, where Black, Latinx and immigrant New Yorkers can live – not just in restricting where they have access to move into, but, just as crucially, in impeding where they have the right to stay. Communities of color have been historically marginalized in access to housing, good jobs, and equitable wages – much of this through direct discrimination and through subtler methods like not producing housing that is affordable to a majority of households of color. Our planning decisions have been complicit in failing to address this, either by making white neighborhoods accessible to residents of color, or in ensuring that residents of color can remain as their neighborhoods gentrify. In many cases, it’s not right to even call these failures – exclusion is often the obvious outcome, and sometimes the stated intention, of our planning decisions. An obvious example is red-lining, when residential segregation was enshrined through active disinvestment in communities of color or the slightest hint of “mixed-race” neighborhoods. But it continues today in an approach to planning that prioritizes creating more housing for white people in low-income communities of color, while declaring whiter, wealthier communities mostly off limits for the amount of affordable housing needed to make them more accessible.

The City’s Decision-Making Process Privileges White New Yorkers

The through line in all of this is that our planning processes and decisions take care of white communities first and foremost. This is done in part by following the dictum that land should be used for its most “desirable” purpose, while ignoring the fact that in this country land has always been most desirable when white people want to live there. That’s the only guarantee. And it means that anything that might change that equation – like housing that can serve a majority of households of color – must be limited. Across various neighborhood typologies, there is a similar theme: there is not enough affordable housing accessible to households of color, or mechanisms the City is willing to use to create and preserve the kind of affordable housing that households of color disproportionately need.

How does this play out in practice? Our planning system generally makes sure that lower density white neighborhoods remain low-density, protecting what is often labeled “neighborhood character”. This may be achieved in part through the use of historic landmark designations (ensuring no larger developments can come in), in part through downzoning selective sections of a neighborhood that generally align with white homeownership, while driving new density to those portions that house people of color, or in some cases retaining single family, suburban style zoning regardless of a neighborhood’s proximity to transit and other infrastructure. All these tactics ensure that what new development does come to low density white communities is generally too small to require or incentivize affordable housing through zoning, tax incentives, or subsidy programs.

In higher density white neighborhoods, little is done to ensure that affordable housing is provided on a scale commensurate with new development. Tax abatements like 421-a (Affordable New York) give far too much profit and savings to developers and luxury condo owners in exchange for affordable housing that is not broad or deep enough in reach. In our highest density zoning districts, the de Blasio Administration refuses to apply its primary affordable housing zoning tool – Mandatory Inclusionary Housing – leaving large swathes of these dense, white, and wealthy communities exempt. The only zoning option that does provide affordable housing here allows developers to build 20% bigger in exchange for less than 5% of the apartments being affordable (and there’s a special district along Fifth and Park Avenue that removes even that possibility for providing affordable housing, in part to preserve “neighborhood character”). Even where the City has the potential to increase density to provide at least the possibility of affordable housing, they refuse to do so. In Soho, the City is considering a rezoning to make retail development easier in this high-end commercial district. What’s not in the proposal? Increasing residential density so Mandatory Inclusionary Housing would apply, providing at least some affordable housing, at no cost to the city, in an area where zero affordable units have been built to date under the de Blasio Administration.

The similarity in both these types of white neighborhoods – high or low density – is that any new development primarily serves the existing demographics and does not seek to make the neighborhood more accessible to others. It’s a different story in low-income communities of color that white people want to live in (and developers want to make more money in); then our planning system primarily works to ensure that space is opened up to accommodate incoming white people, primarily through upzonings that can bring in larger luxury developments. Many times, these planning decisions “follow the market” – looking to increase housing options for whiter and wealthier residents in neighborhoods where gentrification is already starting to take place. This gives the City cover in a sense, allowing them to present gentrification and displacement as inevitable. The best option for communities of color, the City says, is to accept new density – even if most of it is not intended to serve them – with a small percentage that will be affordable, even if much of that is still at rents out of reach for a majority of current residents. If gentrification is coming no matter what, the proposed solution is to accelerate it in exchange for a small amount of affordable housing and long-needed capital investments that will largely benefit new residents as the old population is pushed out.

The oft-cited Williamsburg/Greenpoint waterfront rezoning is a classic example of this approach: a rezoning following the market after it had started to do its gentrification work. The City’s response to growing real estate pressure and the threat of displacement was to help it along with new capital investments and increased density for luxury developments, with a smattering of affordable units. The City now likes to cite that this rezoning has “stabilized” the neighborhood by providing affordable units that helped stop the demographic changes that were already taking place. But this gives the game away – imagine what could have been done if the City had actually tried to address the displacement from the beginning; if it had worked to curb market forces and implemented an actual plan for the households of color who lived there already to remain and thrive. That “stabilization” they cite was a secondary effect of the Williamsburg rezoning, but it was never its intended primary goal, which remains the creation of thousands of new luxury apartments out of reach for most households of color.

Planning Isn’t Color-Blind – Racial Equity Should Be at the Center of the Planning Process

This illustrates one of the central tensions in the City’s current planning process: the color-blind belief that their approach can be a win-win for everyone, that you can prioritize the development of market-rate housing in communities of color and as long as some affordable housing units are provided, everybody benefits. But this is simply not true; in the absence of explicit racial-equity priorities, white residents and white communities will always benefit the most. The City’s current approach to rezonings makes this clear – essentially replicating the Williamsburg model by “following the market” (or in some cases helping to jumpstart the market) into communities of color elsewhere like from East New York to East Harlem to Jerome Avenue – with the same story: gentrification is coming no matter what and you should get what they can, while they still can. Communities of color end up with a false choice: either allow the City to help drive market forces that will in turn push them out of their neighborhoods or lose out on the chance to access capital investments – investment that are long overdue to serve existing residents.

This is a choice that most white communities simply don’t have to face. Investments in their neighborhood are not contingent on providing new density that will not serve them – in this case by making their neighborhoods more accessible to households of color; in fact all the tools of planning work to ensure that their neighborhoods continually serve white residents, just as all the tools of planning work to ensure that white households are served when they want to move into communities of color. Soho can say no to more affordable housing; parts of the Upper East Side can retain their special district that specifically limits it. But when a neighborhood like Williamsburg, East New York, or East Harlem is worried about displacement, the answer is to help create primarily market-rate housing.

Overcrowding among households of color is a direct outcome of this kind of approach, as they are left with an ever more limited and geographically restricted supply of housing that is accessible to them. And overcrowding in communities of color is one of the clearest correlations with the disparate impact COVID-19 has had on Black, Latinx, and immigrant New Yorkers.

While these outcomes are utterly predictable based on the City’s approach to planning, that does not make them inevitable. If anything, this health crisis – on top of the affordability crisis and lack of economic opportunity communities of color already faced – should highlight the urgency of making wholesale changes in the way New York City does planning. There is another way forward – it involves putting racial equity at the center of the planning process. It would mean prioritizing the needs of low-income communities of color above those of white communities that benefit from the current approach. It would mean refusing to let the burden of solving citywide problems fall on low-income communities of color. It would mean planning that places the interests of the vast majority of New Yorkers above those of the real estate industry. We need a planning approach that seeks to expand the limits of the possible, instead of our current system that works hard to defend those limits, never straying from the tight parameters of the existing paradigm.

A good place to start is the principles of the Thriving Communities Coalition (TCC), of which ANHD is a founding member. TCC seeks a planning process that addresses the needs of low-income communities and communities of color by centering on the principles of:

- Fair distribution of resources and development

- Enforceable commitments – no more empty promises

- Integration without displacement

- Transparency and accountability

- Real community power and ownership

There’s no rule that says planning has to be done the way we do it here. Despite the weight of history behind it, this continued approach persists because it’s what people in power have decided planning means, and they are holding very tightly to that stance. But now is the time to confront the need for systemic change, to acknowledge that the tools of racism and white supremacy don’t operate in isolation. Planning that does not forcefully center racial equity as its primary goal – that does not consciously seek to address and undo its historic legacy – is planning that is complicit.