Key Findings

Overall, New York City saw a 2% rise in total business creation over the past five years. This means that there were slightly more businesses in the City in 2016 than there were in 2011. While the percentage of businesses in New York grew over the course of five years, net change varied widely by neighborhood.

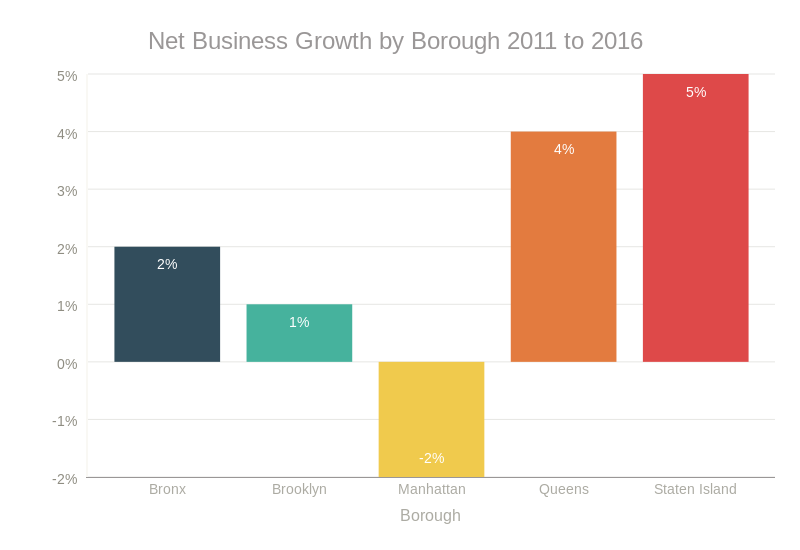

Manhattan as a whole experienced the most decline in total business, with every neighborhood except Chelsea and Central Harlem experiencing a net loss in businesses. Queens and Staten Island saw the most net growth, with a 4% and 5% rise in businesses overall, while total businesses in Brooklyn and the Bronx grew by a smaller 1% and 2%, respectively. While the outer boroughs all saw a net increase in businesses, Manhattan experienced a 2% net loss, with the greatest decrease in businesses concentrated in Stuy Town and in the Upper East Side. As New York’s neighborhoods change, the City needs to ensure that long-standing businesses have the necessary support and opportunity to survive and thrive.

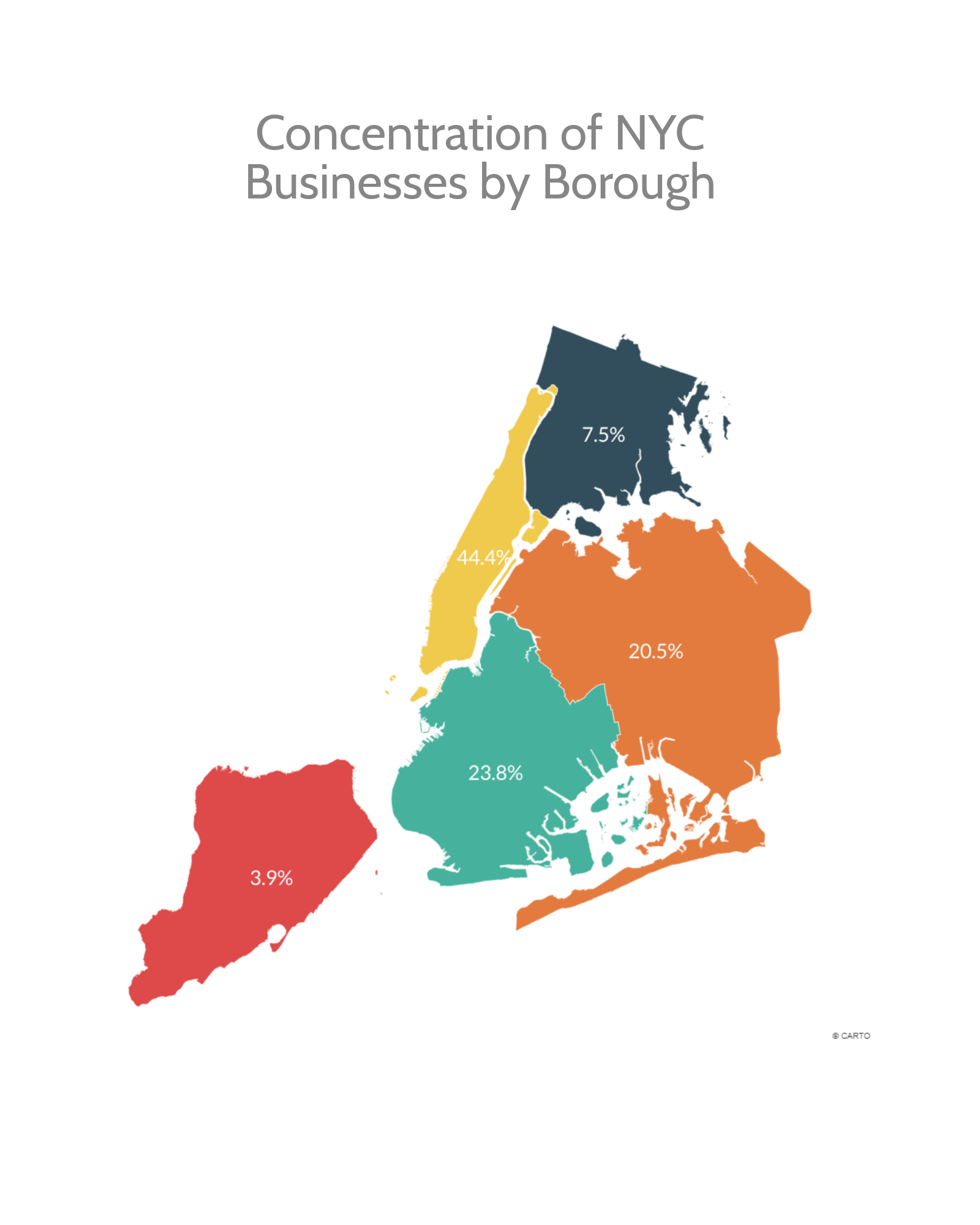

Manhattan is still home to the largest concentration of businesses in the City, with 44.4% of all of New York businesses located in the borough. Brooklyn follows with 23.8% of businesses and Queens follows close behind with 20.5% as home to all New York firms. The Bronx and Staten Island lag much further behind, home to only 7.5% and 3.9% of all of New York City’s businesses.

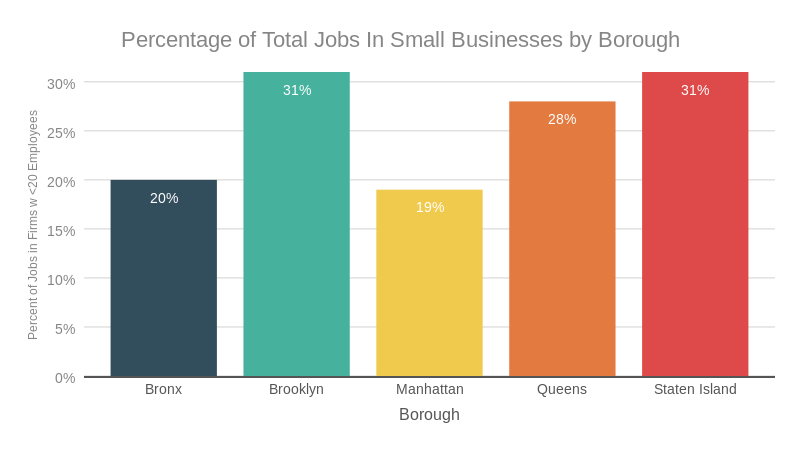

Tracking changes in businesses by neighborhood is crucial, especially changes in small businesses, since 26% of all jobs in New York City are at firms with 20 or fewer employees. In immigrant and majority people of color neighborhoods, employment in small businesses tends to be much higher.

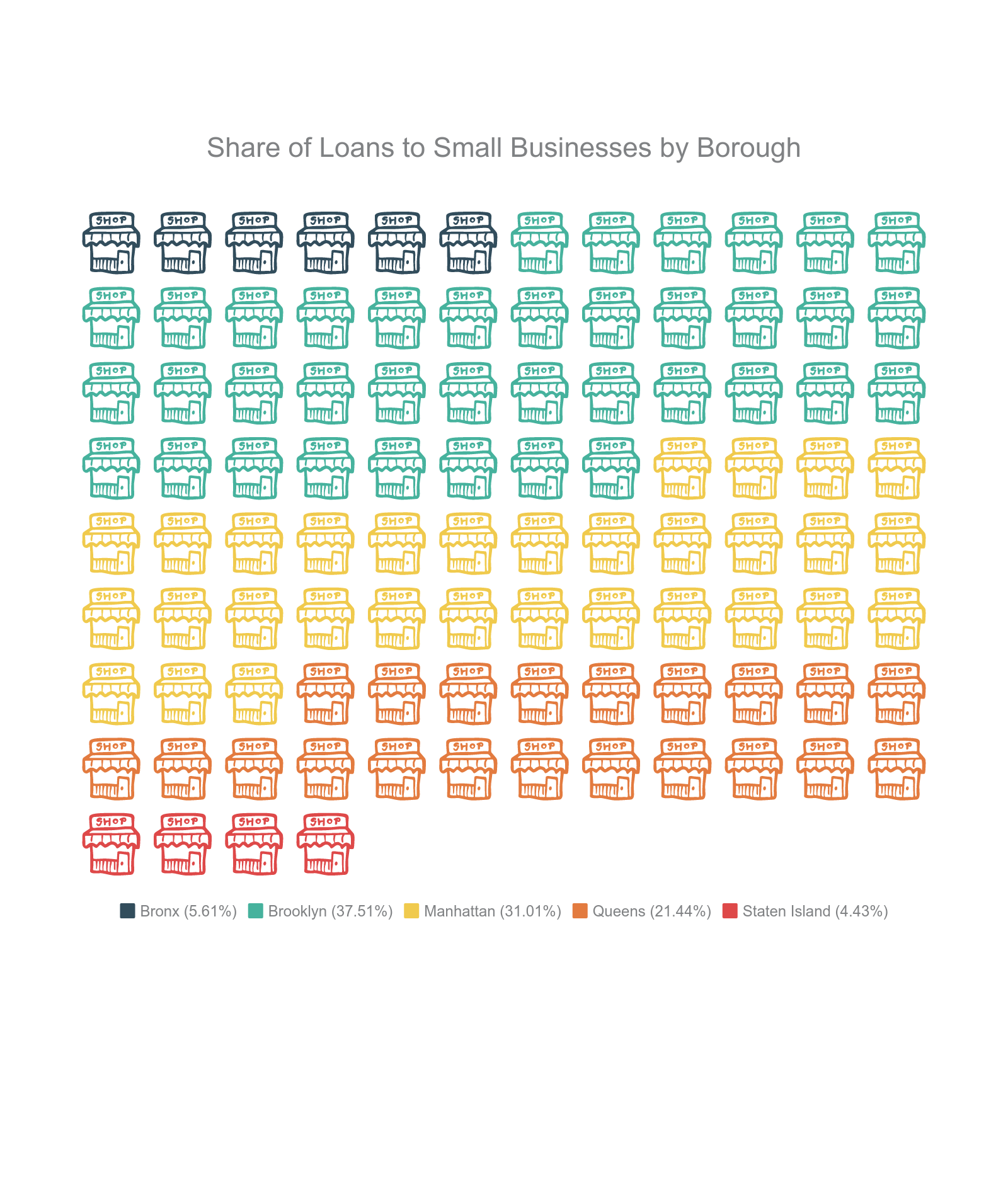

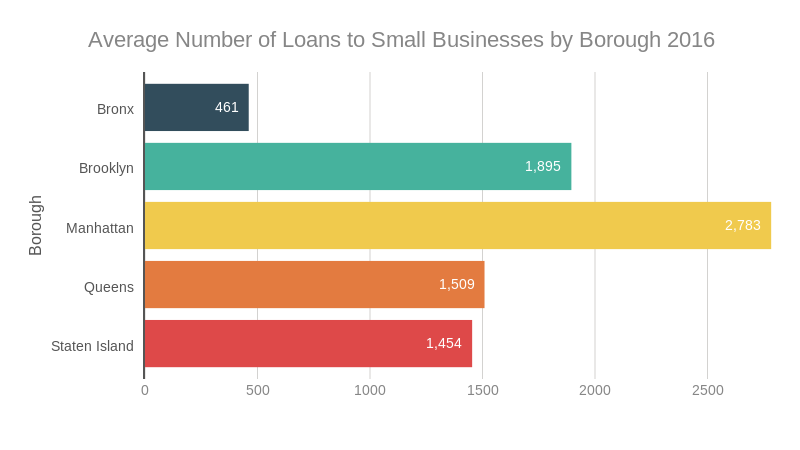

Businesses in the outer boroughs still receive much fewer small business loans, at half the rate of Manhattan businesses, which received an average of 2,783 loans. Bronx businesses received the fewest loans at an average of 439 loans across the borough, while Brooklyn, Queens, and Staten Island fared better with a respective borough-wide average of 1,742, 1,509, and 1,454 businesses receiving loans. Outside of the Bronx, Brownsville and East Harlem similarly received among the fewest loans citywide, at 260 and 635 respectively — much lower than the citywide average of 1,623 loans. This pattern suggests that communities of color, in particular communities in the Bronx and upper Manhattan, are losing access to localized economic development and opportunity. The lack of small business financing in these neighborhoods means a lack of small business jobs, which are sorely needed in communities with among the highest rates of unemployment in the city. Small business loans must be made accessible to all of New York’s communities — not just it’s wealthiest.

The displacement of neighborhood institutions not only threatens New York’s identity, but also eliminates jobs, community spaces, and affordable resources in low- and moderate-income communities of color. As the city’s small businesses disappear at an alarming rate, it is vital to implement robust protections to ensure their survival, and in turn ensure the vitality and vibrancy of New York’s neighborhoods.

Data

Though this analysis provides a cursory overview of New York’s small business landscape citywide, data on small firms is very limited. Census-level information data relies on local, state, and federal administrative sources and does not capture unlicensed businesses, which tend to be located in the City’s most vulnerable commercial corridors.

Analysis

Using the same DCA data, net percent change, or total change in the number of licensed operating businesses across the city in 2011 and 2016, was calculated. Net percent change takes into account new licenses, or new businesses that replaced permanently shuttered shops. Overall, New York City saw a 2% rise in total business creation over the past five years. This means that there were slightly more businesses in the City in 2016 than there were in 2011. While the percentage of businesses in New York grew over the course of five years, net change varied widely by neighborhood. Manhattan as a whole experienced the most decline in total business, with every neighborhood except Chelsea and Central Harlem experiencing a net loss in businesses. Queens and Staten Island saw the most net growth, with a 4% and 5% rise in businesses overall, while total businesses in Brooklyn and the Bronx grew by a smaller 1% and 2%, respectively. While the outer boroughs all saw a net increase in businesses, Manhattan experienced a 2% net loss, with the greatest decrease in businesses concentrated in Stuy Town and in the Upper East Side. Though Manhattan as a borough saw the most in net loss of businesses, the largest decline in businesses over the course of five years was concentrated in Hunts Point, which saw a 6% loss.

This may be attributed to the epidemic of commercial warehousing, or the process in which landlords hold on to property without renting it out in hopes that its rental value might rise. Landlords hold onto vacant spaces and wait for real estate prices to rise, so they can rent the property to a newer and wealthier clientele. Currently, no penalty exists for property owners who neglect vacant properties or intentionally leave space vacant. This leaves storefronts vacant and businesses who can’t afford high rents priced out. In order to create commercial affordability, the City must ensure that landlords who warehouse properties are held accountable, whether through fines or increased taxation on properties left unrented for over six months.

However, it should be noted that despite the decrease in businesses, Manhattan is still home to the largest concentration of businesses in the City, with 44.4% of all of New York businesses located in the borough. Brooklyn follows with 23.8% of businesses and Queens follows close behind with 20.5%. The Bronx and Staten Island lag much further behind, home to only 7.5% and 3.9% of all of New York City’s businesses. The comparatively low percentage of businesses in these boroughs is alarming. It means there are less local job opportunities, less places for community convening, inconvenient options to purchase necessities, and much fewer opportunities to circulate capital within local communities.

However, it should be noted that despite the decrease in businesses, Manhattan is still home to the largest concentration of businesses in the City, with 44.4% of all of New York businesses located in the borough. Brooklyn follows with 23.8% of businesses and Queens follows close behind with 20.5%. The Bronx and Staten Island lag much further behind, home to only 7.5% and 3.9% of all of New York City’s businesses. The comparatively low percentage of businesses in these boroughs is alarming. It means there are less local job opportunities, less places for community convening, inconvenient options to purchase necessities, and much fewer opportunities to circulate capital within local communities.

Although new growth bodes well for most of the City, it is critical to consider who replaced what. In low- and moderateincome communities of color and immigrant communities, increases in businesses is a good sign — but the growth, stability, and longevity of long-term businesses must be taken into account. Although areas such as Astoria and Sunset Park saw net gains in businesses, they also had some of the highest rates of expirations of existing businesses in the city, at 4% and 2% respectively. Jackson Heights, which had among the greatest growth in business licenses, also saw 2% of existing business licenses expire in the period between 2011 and 2016. As New York’s neighborhoods change, the City needs to ensure that long-standing businesses have the necessary support and opportunity to survive and thrive.

Although new growth bodes well for most of the City, it is critical to consider who replaced what. In low- and moderateincome communities of color and immigrant communities, increases in businesses is a good sign — but the growth, stability, and longevity of long-term businesses must be taken into account. Although areas such as Astoria and Sunset Park saw net gains in businesses, they also had some of the highest rates of expirations of existing businesses in the city, at 4% and 2% respectively. Jackson Heights, which had among the greatest growth in business licenses, also saw 2% of existing business licenses expire in the period between 2011 and 2016. As New York’s neighborhoods change, the City needs to ensure that long-standing businesses have the necessary support and opportunity to survive and thrive.

Tracking changes in businesses by neighborhood is crucial, especially changes in small businesses, since 26% of all jobs in New York City are at firms with 20 or fewer employees, according to U.S. Census data. In immigrant and majority people of color neighborhoods, employment in small businesses tends to be much higher.

The share of small businesses in a neighborhood varies widely. Neighborhoods like Crown Heights, Chinatown, Jackson Heights, and Great Kills all have over 30 percent of their local employment in firms with less than 20 employees; whereas the Financial District, Midtown, Morningside Heights, and Morris Park all had among the City’s lowest rate of employment in small businesses, below 13 percent. It is important to note that this data relies on local, state, and federal administrative sources and will likely not capture any unregistered or unlicensed businesses that are more prevalent in immigrant and low-income communities.

The share of small businesses in a neighborhood varies widely. Neighborhoods like Crown Heights, Chinatown, Jackson Heights, and Great Kills all have over 30 percent of their local employment in firms with less than 20 employees; whereas the Financial District, Midtown, Morningside Heights, and Morris Park all had among the City’s lowest rate of employment in small businesses, below 13 percent. It is important to note that this data relies on local, state, and federal administrative sources and will likely not capture any unregistered or unlicensed businesses that are more prevalent in immigrant and low-income communities.

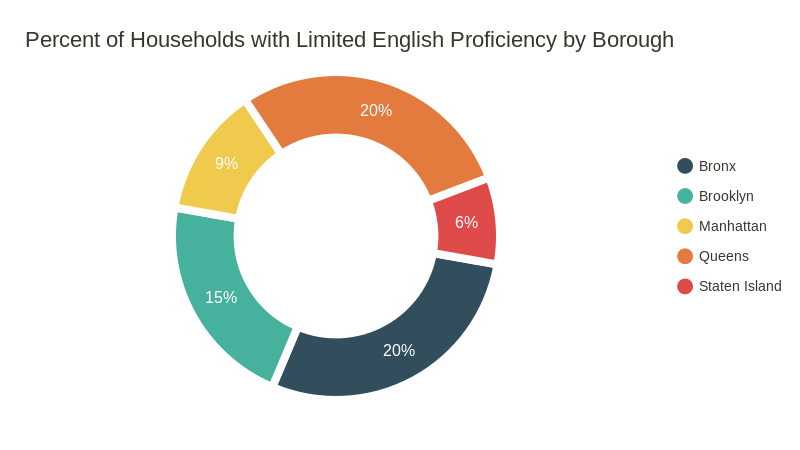

In Crown Heights, which saw a 2% loss in net businesses, 49% of all jobs are within small businesses. And 48% of jobs in that neighborhood are held by nonwhite workers. Thirty-one percent of total employment in Flushing is in small businesses, while 49% of all the jobs in that neighborhood are held by nonwhite workers. 44% of the community is comprised of limited English speaking households, meaning that a large percentage of the people living in that neighborhood are immigrants of color employed at small businesses. Similarly, in Jackson Heights 36% of all jobs are at small businesses, with 33% of households having limited English proficiency. Small businesses are the backbone of the neighborhood economy in immigrant communities and communities of color. In order to guarantee economic opportunity to all New Yorkers, these businesses and the commercial corridors they exist within must be protected.

Neighborhoods with lower rates of employment at small businesses are heavily clustered in the Bronx and in Upper Manhattan. Most of these areas are also neighborhoods where small businesses have received among the lowest number of loans citywide.

Neighborhoods with lower rates of employment at small businesses are heavily clustered in the Bronx and in Upper Manhattan. Most of these areas are also neighborhoods where small businesses have received among the lowest number of loans citywide.

Access to capital is critical for small businesses to launch, stay open and grow. However, small businesses and in particular small businesses in low- and moderate-income communities of color face barriers in accessing financing from traditional banks. As a result, they are often forced to borrow from friends and family; use personal savings; defer investment; or turn to less-regulated, higher cost, sometimes predatory online lenders. This leaves business owners, especially immigrant business owners, in a precarious state. Limited small business loans mean fewer small businesses, which leaves residents of entire neighborhoods not only without access to basic necessities, but also without the opportunity to circulate capital within their own communities.

Access to capital is critical for small businesses to launch, stay open and grow. However, small businesses and in particular small businesses in low- and moderate-income communities of color face barriers in accessing financing from traditional banks. As a result, they are often forced to borrow from friends and family; use personal savings; defer investment; or turn to less-regulated, higher cost, sometimes predatory online lenders. This leaves business owners, especially immigrant business owners, in a precarious state. Limited small business loans mean fewer small businesses, which leaves residents of entire neighborhoods not only without access to basic necessities, but also without the opportunity to circulate capital within their own communities.

Small business loan information is based on recently released FFIEC data. The FFIEC definition for a small business is any businesses with under a million dollars in annual revenue. Kingsbridge, where 13% of jobs are in small businesses with 20 or fewer employees, only received 430 small business loans in 2016, less than even a third of the average number of loans given citywide. This pattern holds true across the Bronx, which received the least number of loans of any borough. University Heights received only 328 small business loans, among the fewest of any neighborhood in the city. Only 15% of all jobs in the area are at small firms, among the lowest rates in the city.

Outside of the Bronx, Brownsville and East Harlem similarly received among the fewest loans citywide, at 260 and 635 respectively — much lower than the citywide average of 1,623 loans. In both neighborhoods, jobs at small businesses are few and far between, with only 17% and 11% of total employment at small businesses. Conversely, areas with the highest number of small business loans — Chelsea, the Financial District, Greenwich Village — also tend to have lower than average employment in small businesses. This pattern suggests that communities of color, in particular communities in the Bronx and upper Manhattan, are losing access to localized economic development and opportunity. The lack of small business financing in these neighborhoods means a lack of small business jobs, which are sorely needed in communities with among the highest rates of unemployment in the city. Small business loans must be made accessible to all of New York’s communities — not just it’s wealthiest.

Conclusion

New York City’s true success hinges on ensuring that all its residents have access to opportunity and community resources and that its small businesses have access to protections and city resources. In order to create truly equitable economic development, it is crucial to protect New York City’s small businesses, especially those owned and operated by immigrants and people of color. That includes more funding for resources for existing small businesses, fines for landlords who raise rents and then leave vacant storefronts empty, and the creation and maintenance of affordable commercial spaces.

The displacement of neighborhood institutions not only threatens New York’s identity, but also eliminates jobs, community spaces, and affordable resources in low- and moderate-income communities of color. As the city’s small businesses disappear at an alarming rate, it is vital to implement robust protections to ensure their survival, and in turn ensure the vitality and vibrancy of New York’s neighborhoods.