Summary

While economic development programs over the last three years have focused on COVID-related recovery, for many of New York City’s small businesses in communities of color and immigrant neighborhoods, a recovery to pre-pandemic conditions has not happened. Moreover, a return to a pre-pandemic baseline would be insufficient to ensure the survival and success of the small businesses that constitute the cultural fabric of our neighborhoods. Especially in our immigrant communities and communities of color, residents rely on their local businesses for essential, culturally relevant goods and services, as well as jobs.

ANHD’s new analysis of both citywide data and a survey of 121 merchants who own storefront businesses shows that threats to small businesses are consistently higher both in communities of color and to small business owners who are people of color and immigrants themselves.

Where do we go from here?

Keeping a storefront business alive means not only running a successful operation, but combating speculation, harassment, and displacement threats on multiple fronts. Without adequate protections and resources, the commercial tenants who provide essential goods and services to their communities face just as much displacement risk as residential tenants.

Programs like Commercial Lease Assistance work, but need more resources and need to be strengthened. We must also organize merchants to shift power to our small businesses so that they can fight for more proactive tenant rights, legal resources, and policies that stabilize and support them. ANHD and our partners have begun this work and will continue to fight for the rights of commercial tenants and all of New York City’s smallest businesses.

Why this matters

Small businesses are the backbone of New York City. Of its approximately 220,000 businesses, 89% have fewer than 20 employees. Small storefront businesses – such as eateries, bodegas, hair salons, laundromats – make up the cultural fabric of our neighborhoods: especially in our immigrant communities and communities of color, residents rely on their local storefronts for essential, culturally relevant goods and services, as well as jobs. But those essential businesses are under dire threat, due to the systemic lack of protections and power imbalance between small business owners and their landlords.

ANHD’s new analysis of both citywide reporting and a survey of 121 merchants who own storefront businesses shows that threats to small businesses are consistently higher both in communities of color and to small business owners who are people of color and immigrants themselves.

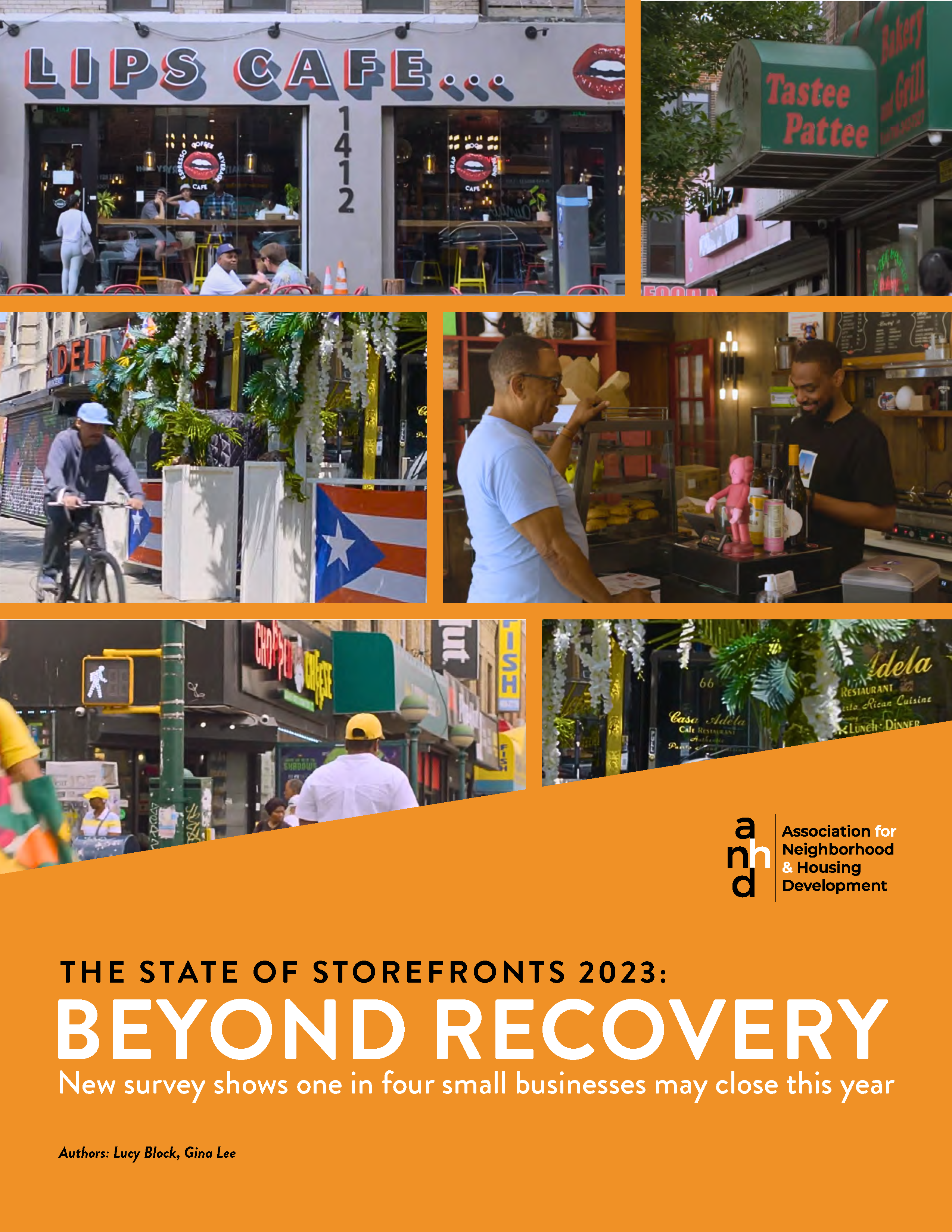

During a time of great economic hardships caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, real estate speculation has driven a rapid rise in rent in many communities of color and immigrant communities. ANHD’s analysis shows that commercial rents have risen vastly beyond pre-pandemic levels, which were already burdensome for many small businesses. These rising rents are more prevalent in communities that are predominantly people of color.

Within a landscape of rapidly rising rent, the lack of structural protections for commercial tenants puts small businesses at the mercy of the speculative rent market and multiple forms of harassment and displacement pressure. Many commercial tenants do not have a lease, even those in business for decades in the same location; those businesses are ineligible for many grant and loan programs. Our survey showed that our neighborhoods’ critical small businesses are facing multiple threats of closure and relocation, rising rents, rent and utility debt, personal liability for rent, and tenant harassment.

While economic development programs over the last three years have focused on COVID-related recovery, for many of New York City’s small businesses in communities of color and immigrant neighborhoods, a recovery to pre-pandemic conditions did not occur. Furthermore, a return to a pre-pandemic baseline would not be sufficient for these businesses to survive and thrive. Prior to the pandemic, many storefront businesses were already struggling to keep up with rising costs and facing severe displacement pressure.

In addition to rising costs, opaque systems and a lack of resources and support create an additional burden, particularly on business owners who are immigrants and people of color. Language access and targeted outreach are necessary for many of these business owners to learn about and successfully apply for grant programs. They may be turned away from traditional banks and have trouble finding alternative lending options to finance their businesses. Undocumented business owners, of which there are an estimated 48,000 in New York City, face particular challenges in accessing capital due to a lack of formal credit, among other challenges. On top of that, as commercial tenants negotiating lease terms, they may speak a different primary language from their landlord’s, making an already imbalanced relationship even more challenging.

While this report focuses on commercial tenants, they are not the only small businesses that are critical to our neighborhoods’ functioning: street vendors face myriad threats to their survival as well, such as overpolicing and lack of access to permits. The threats to commercial tenants and street vendors are intertwined; when investors gamble their capital on the gentrification and heightened value of land in a neighborhood, it leads to the displacement of tenants, businesses without a brick and mortar space, and residents alike. We maintain that the stabilization of our small businesses is a critical component of the health of our neighborhoods and communities.

The ecosystem of a healthy commercial corridor includes storefront small businesses, street vendors, and local residents, all of whom face displacement risks and need protection. To address this instability in New York City’s commercial corridors, a framework of recovery is not enough. We must build the power of commercial tenants who fuel our neighborhoods but lack legal protections and face grave displacement pressure. Organizing merchants as a group with shared political identity and interests can shift the focus of economic development beyond just recovery to one that centers the health of the critical small businesses that make up the fabric of our neighborhoods.

Our research approach

Organizing by ANHD and the United for Small Business NYC coalition (USBnyc) enabled the creation of a storefront registry that has tracked storefront vacancies and aggregate rents since 2019, allowing for important citywide analysis. Yet the aggregated data, as is the case with all quantitative data, only shows part of the picture.

With the support of New York City Small Business Services (SBS), ANHD launched the Citywide Merchant Organizing Project (CMOP) in 2022. ANHD and our partners surveyed 121 merchants, almost all of them commercial tenants.

This report includes both quantitative analysis of data from the City’s storefront registry and original survey data collected by ANHD’s merchant organizing partners. Together, findings from these two datasets paint a picture of a particularly challenging landscape for small businesses in communities of color and immigrant communities.

What we found: storefront registry data

Storefront registry data shows large increases in rents, particularly in communities of color.

Since ANHD and USBnyc won the passage of Local Law 157 in 2019, the Department of Finance has published statistics on vacancies, median rents, and other metrics for ground-floor and second-floor commercial spaces in most of New York City. This data is aggregated at the council district level, allowing us to see trends since 2019. ANHD first published an analysis of rent trends, as well as vacancies, in our 2022 State of Storefronts report. Our 2023 analysis examines changes from 2019-2021, the most recent data available, allowing us to see the changes in citywide rents well into the height of the pandemic.

Analysis of this data indicates that commercial rents overall in New York City continued to rise despite the economic impacts of COVID-19. The pandemic caused major losses in revenue for countless small businesses, many of whom are also commercial tenants. Borough and council district breakdowns of the data reveal the uneven landscape of rent increases throughout the city.

Citywide, storefront rents increased 10.9% between 2019 and 2021, but those increases were uneven.

Manhattan is the only borough in which storefront rents declined from 2019 to 2021. Median monthly rents started much higher in Manhattan, at $9.00 per square foot, versus less than $4.00 per square foot in other boroughs. This could indicate that Manhattan rents were over-valued before the pandemic; in fact, speculative warehousing of storefronts was a major concern. It is also due to large-scale office closures and many offices shifting from in-person to remote or hybrid work.

Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx all saw significant increases in median storefront rents despite the economic downturn of the pandemic. Those boroughs had monthly median rents ranging from $3.00 per square foot in the Bronx to $3.67 per square foot in Queens in 2019, and the borough-wide increases ranged from 9.0% in Queens to 22.9% in Brooklyn.

At a council district level, increases occurred primarily in Upper Manhattan, the Bronx, Queens, and Brooklyn.

The council districts with the largest rent increases were distributed across Queens, the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Upper Manhattan:

-

District 31 in Rockaway, Queens, at 37.5%

-

District 16 in the Highbridge, Grand Concourse, and Crotona neighborhoods of the Bronx, at 33.3%

-

District 33 spanning Greenpoint to Downtown Brooklyn, at 28.5%

-

District 19 in Northeast Queens, at 25.3%

-

District 9 in Central Harlem, at 25.0%

This more granular view offers more nuance than the borough-wide level, which showed a rent decrease overall for the borough of Manhattan. However, Upper Manhattan, which is both lower-income and home to more people of color than the rest of the borough, also saw major increases in rents: 7.5% in Council District 10 (Washington Heights and Inwood) and 25% in District 9 (Central Harlem).

More people of color live in areas of New York City where storefront rents increased during the pandemic.

In districts where rents increased from 2019-2021, 72.1% of the population identifies as a person of color, compared to 47.2% of the population in districts where rents decreased during that period. This disparity points to the particularly forceful displacement pressure experienced by communities of color in gentrifying neighborhoods, many of which were historically redlined and disinvested. Rising commercial rents contribute to the displacement of small businesses that provide culturally-specific goods and services in these communities. This mirrors the pattern we encountered in last year’s report, which also showed a major disparity in the racial demographics of council districts where rents increased versus where they decreased.

What we found: CMOP survey data

The small businesses we surveyed face dire displacement threats, and merchants of color and immigrant merchants face particular challenges.

Since 2022, ANHD’s Citywide Merchant Organizing Project has worked toward furthering merchant organizing to strengthen the stability of New York City’s commercial corridors and prevent the displacement of culturally relevant small businesses and local jobs. CMOP aims to build a strong citywide base of merchants ready to fight against displacement threats.

From 2022-2023, CMOP groups worked across five neighborhoods to administer 121 merchant surveys, co-designed with organizers and merchant leaders, to gather data on the ground about the challenges facing New York City’s small businesses and provide a more nuanced picture than citywide reporting data allows. The surveyed neighborhoods include Jackson Heights, Elmhurst, and Far Rockaway in Queens; Lower East Side/East Village in Manhattan; and the Little Yemen neighborhood of the Bronx. These are neighborhoods of great cultural importance to New York City’s communities of color and immigrant communities, where community groups have witnessed displacement pressures play out over many years. The community groups who administered the survey include Asian American Federation, Chhaya CDC, Cooper Square Committee, Rockaway East Merchants Association (REMA4US), and the Yemeni American Merchants Association.

As their rents rise, merchants in these neighborhoods have struggled to keep their doors open. Many have managed to do so despite inadequate physical conditions in their storefront spaces, difficult relationships with their landlords, ineligibility for grant and loan programs, and a severe lack of accessible resources. As a result of ANHD and USBnyc’s organizing efforts, commercial tenants have only recently gained some protections against landlord harassment and abuse of power: namely, the commercial tenant anti-harassment law first passed in 2016 and expanded in 2019. However, without an adequate mechanism for enforcement of this law, commercial tenants are severely limited in their means of recourse and ability to pursue legal action. The result is that many commercial tenants still experience landlord harassment – both within and outside of the definition of harassment set forth in the law – that puts their business operations at risk and contributes to displacement pressures.

For these merchants, answering survey questions about their rents and leases could feel risky, as they feared retaliation from their landlords. Merchant organizers who administered the survey first had to establish trust and build relationships with the merchants; this took many outreach attempts, sometimes over the course of years leading up to the survey. On-the-ground merchant organizing and small business support services were essential to the success of this research effort.

The CMOP survey takes us deeper into the experiences of merchants who do business in the corridors that are experiencing displacement pressures such as rising rents, poor conditions, and a lack of security without a long-term lease. These merchants find themselves in increasingly vulnerable positions from which they work to maintain their livelihoods and support the cultural and social fabric of their neighborhoods.

The CMOP survey results revealed that across multiple culturally important commercial corridors, small business owners – and particularly merchants of color and immigrant merchants – face multiple severe displacement threats.

Of all surveyed businesses:

-

1 in 4 merchants plans to or may close in the next year

-

More than 1 in 3 merchants plans to or may relocate in the next year

-

3 in 5 merchants had their rent increase more than 10% in the last year

-

More than 1 in 3 merchants owed back rent and more than 1 in 4 owed utilities

-

Almost 1 in 5 merchants have experienced a form of harassment by their landlord

-

Almost 9 in 10 are personally liable for their rent

-

9 in 10 have a lease

Among many alarming results, the following stood out to us. A quarter of all surveyed businesses told us they plan to or may close in the next year, and 37.0% of them said they plan to or may relocate. Those numbers represent serious instability and threats to the vitality of these commercial corridors.

Rising rents were extremely common: despite the majority holding leases, 61.1% of businesses said their rent had increased at least 10% in the previous year. Therefore, these businesses mirrored the picture we saw in citywide data where storefront rents increased disproportionately in areas outside of “core” Manhattan and communities of color.

With rapidly rising rents and the major losses of revenue small businesses faced during the height of the pandemic, it is unsurprising that 35.3% owed back rent and 27.6% owed utilities. At the same time, the vast majority (88.5%) of businesses are personally liable for any rent owed. This is often a condition of their lease or other rental agreement because they have too few assets in their businesses’ names. If the business must close, the owner is personally on the hook for rent. Merchants may have to dip into their personal savings to make such payments because a failure to do so would allow the landlord to take legal action against them.

Despite being made illegal by the 2016 commercial tenant anti-harassment law, commercial tenants continue to face serious harassment. Seventeen merchants out of 93 who responded to the question (18.3%) reported having experienced one of the following types of harassment, totaling 43 instances:

Despite the many indications of great displacement risk for small businesses in the corridors we surveyed, we believe our survey may underestimate displacement risk due to the high proportion of lease-holders in our survey sample.

A very large portion (91.7%) of surveyed businesses held leases. In the experience of ANHD and other organizations fighting small business displacement, our neighborhoods’ most marginalized businesses frequently do not have leases. One organizer confirmed that businesses he attempted to survey who did not have leases were almost uniformly unwilling to participate. We believe that generally speaking, the businesses who were more likely to participate in our survey were more secure and less at-risk than many others who we are fighting to keep in our communities. Therefore, we believe that despite the alarming displacement risks we found in our survey results, that these numbers underestimate overall risk in these communities.

Leases and commercial lease assistance make a difference.

At the same time, our survey clearly showed that those who have leases are not immune to displacement threats. Among the many threats that merchants reported despite the high rate of leases, 32.6% reported that they felt coerced to change their lease terms during the pandemic due to missed payments. Language barriers also played a significant role: 46.3% of small business owners who speak a different first language than their landlord reported feeling coerced to change their lease terms during COVID, more than double the rate (20.8%) of small business owners whose landlords speak the same language as them. Small business owners who identify as immigrants were similarly twice as likely to have felt coerced to change their lease terms: 39.0% compared to 23.5% of non-immigrants.

Considering this power imbalance, the Commercial Lease Assistance (CLA) Program, the city’s free legal services program for navigating commercial leases, is an important resource for small business owners and other commercial tenants. Survey results show that the program makes a difference in tenant-landlord interactions and lease negotiations. Among those merchants surveyed, two-thirds were aware of the CLA Program, largely due to their work with the community groups and organizers who administered this survey. Merchants who know about the CLA Program were about half as likely as those who do not know about it to report feeling coerced to change their lease terms during COVID (25.0% versus 48.1%) and about twice as likely to report a positive experience negotiating a lease (34.5% versus 18.5%).

Spotlight: Lucy's Flower Shop

In the Kingsbridge neighborhood of the Bronx, where the City is, for the third time, undertaking a redevelopment process for the Kingsbridge Armory, merchants are organizing to resist the displacement that often comes with large-scale redevelopment. Many of the merchants who own storefront businesses do not have a lease and are constantly negotiating rent increases with their landlords. Without a lease, they may face untenable increases if the Armory redevelopment triggers upward rent pressures.

One of these merchants is Lucy, who owns Lucy’s Flower Shop.

“We haven’t had a lease for many years…They threatened us that they were going to get rid of us, and it was traumatic because we didn’t know where we were going to go.”

Spotlight: Casa Adela

In the Lower East Side neighborhood of Lower Manhattan, residents rallied to save Casa Adela, a beloved Puerto Rican restaurant open since 1976, when owner Luis Rivera suddenly faced a 400% rent increase after years of operating without a lease. The lease negotiations took place from 2018 to 2022, when, thanks to organizing and mobilization efforts as well as effective legal support, the property owner agreed to a rent Luis could afford.

“We have the intentions to be here a long time. However, the changes in the neighborhood, in particular the rent changes, is what is really hurting us. The rent has gotten so out of hand that some of us will not be able to make it.”

What we found: disparities

Disparities for merchants of color and immigrant merchants

Within a landscape where commercial tenants have limited ability to negotiate and hold landlords to fair terms, merchants of color and immigrant merchants in particular face the negative effects of landlords’ outsized power. Of all survey respondents, 59.6% self-identified as a person of color and 82.7% identified as an immigrant. Using these responses, we examined disparities among various categories of risk to small businesses.

Note: We received 121 total responses to our survey, but self-identification questions as person of color and immigrant were added partway into surveying; therefore, only 104 merchants responded to these self-identification questions. Where we dis-aggregated data by these identities, we excluded the 17 responses lacking that self-identification.

Merchants of color were more likely to potentially relocate in the next year, be personally liable for rent, owe back rent, owe utilities, and have experienced harassment, and less likely to have a lease.

Merchants who identified as people of color were more likely to face the following displacement threats than merchants who identified as white. They were 27.4% more likely to plan to or potentially relocate in the next year, 41.3% more likely to owe back rent, 68.0% more likely to owe utilities, 17.9% more likely to be personally liable for rent, 90.0% more likely to have experienced harassment, and 7.0% percent less likely to hold a lease.

Immigrant merchants, many of whom are people of color, were more likely to potentially relocate, be personally liable for rent, have had their rent increase at least 10% in the last year, and owe back rent.

Immigrant merchants made up a large portion of respondents: 82.7% of those who self-identified. The displacement threat discrepancies for immigrant merchants were slightly different than those who identified as people of color. Immigrant merchants were 28.8% more likely to plan to or potentially relocate in the next year, 28.0% more likely to have had their rent increase at least 10% in the previous year, 22.6% more likely to owe back rent, and 5.4% more likely to be personally liable for rent versus non-immigrant merchants.

Rent increases since before the pandemic have been uneven across New York City, and neighborhoods where people of color and immigrants live have been more likely to see rising commercial rents. Many of these merchants themselves are people of color and immigrants who have been doing business in their storefronts for decades and are cornerstones of their neighborhoods. These merchants, however, face serious displacement pressure, leading to too much displacement and closures. We need to organize merchants and build a structure of protections and resources so we can keep them in our neighborhoods.

The way forward

Merchant organizing for protections and resources is the way forward

Keeping a storefront business alive means not only running a successful operation, but combating speculation, displacement threats, and harassment on multiple fronts as rents continue to rise. Without adequate protections and resources, the commercial tenants who provide essential goods and services to their communities face just as much displacement risk as residential tenants. The loss of these businesses also contributes to residential displacement, as communities lose the local goods and services that they rely on, have connections to, and can afford.

Our survey showed that resources such as the CLA Program help small business owners; those who knew about the city’s free legal support were half as likely to have felt coerced to change lease terms during COVID-19 and rated their experience negotiating a lease higher. However, the existing funding for the CLA Program is not enough. With more funding and an expansion of the program to include representation in litigation in addition to negotiation, more commercial tenants would be able to negotiate a fair lease and even hold their landlords accountable for violating those terms.

Through the Citywide Merchant Organizing Project, ANHD’s neighborhood-based partners built relationships with and among merchants in commercial corridors throughout the city. Only through organizing with merchants and with their leadership can we start to shift the narrative around small business from one of individual self-reliance to one of collectivity and solidarity. Together, commercial tenants citywide can fight for more proactive tenant rights, legal resources, and policies that shift power to merchants so that we can stabilize and support the small businesses we rely on.

Data tables, methodology, and notes

Storefront registry data analysis: ANHD used Storefront Registration Class 2 and 4 Statistics in order to analyze changes in monthly median rents by council district, borough, and citywide from 2019-2021. Data is pre-aggregated by those geographies based on required reporting for all tax class two and four property owners with ground-floor or second-floor storefronts. Some reporting is required for tax class one properties, but those numbers are very small and excluded from our analysis.

The Department of Finance only publishes rent data at a census tract, council district, borough, and citywide level, obscuring data points for individual storefronts. The data is also based on landlord reporting, which by nature is incomplete. We do not know how many owners of storefront businesses fail to register or correctly report their rents.

Racial demographics: To understand the demographics of districts where rents increased, stayed the same, or decreased during that time period, we used Census Decennial 2020 data on race. Despite limitations in Census data collection and representation among marginalized groups and particular challenges during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, decennial data collects data for the entire population rather than estimating values based on sampling. Therefore, it should be more accurate and does not require the omission of many census tracts due to large margins of error the way that American Community Survey data does. Decennial data collects information on race and ethnicity, but not whether one is foreign-born or their income. Therefore, we limit the demographic analysis in this report to race. In our demographic analysis, we define “people of color” as anyone who identified themselves as a race other than “white alone.” To calculate the share of people of color by council district, we took total values, joined them to 2020 census tract geographies, took the centroids of those geographies, and assigned them to the council district they fell within. We used council district boundaries that are currently accurate, rather than the new boundaries that will take effect on January 1, 2024 as per the redistricting process.

CMOP survey: The CMOP survey was co-designed by ANHD, organizers, and merchant leaders to understand on-the-ground conditions faced by storefront businesses in several culturally important commercial corridors in New York City. The organizations who administered the survey and the surveyed commercial corridors were Chhaya CDC in Jackson Heights, Asian American Federation in Elmhurst, Rockaway East Merchants Association (REMA4US) in Far Rockaway, Cooper Square Committee in Lower East Side/Loisaida/East Village Manhattan, and the Yemeni American Merchants Association in Little Yemen. The survey was administered from October 2022 to January 2023.

View data tables showing the number of respondents and share of respondents for survey questions referenced in this report.

The research team who analyzed results included ANHD’s Senior Research and Data Associate, Lucy Block, the Small Business Services Strategic Impact Grant Coordinator, Gina Lee, and interns Sammi Aibinder and Kellie Marty. The team worked iteratively to identify relevant survey questions and responses to understand the conditions and threats faced by the merchants who responded, and presented early findings to CMOP partner organizations to receive feedback on the analysis.

For more information on our analysis, contact comms@anhd.org.

Acknowledgments

This report was made possible by organizers at Asian American Federation, Chhaya CDC, Cooper Square Committee, Rockaway East Merchants Association (REMA4US), and the Yemeni American Merchants Association, who conducted outreach to storefront small businesses, provided technical assistance and referral services, and coordinated neighborhood-based merchant meetings, all in addition to administering an extensive merchant survey. With funding from the New York City Department of Small Business Services, these five organizations made up the first cohort of ANHD’s Citywide Merchant Organizing Project (CMOP). BKLVLUP and the Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition joined a second phase of the project and also contributed their perspectives to this report.

ANHD is also grateful to our funders, Goldman Sachs and Santander Bank, who support ANHD’s Equitable Economic Development work, including our focus on small business preservation and amplification in BIPOC and low-income neighborhoods. These funders, as well as ANHD’s general operating support funders–the Mertz Gilmore Foundation, Robin Hood Foundation, Scherman Foundation and Trinity Wall Street Foundation–helped make this report possible.