What Happened To Housing Development When 421a Was Suspended?

The real estate industry has long claimed that the 421a tax exemption is absolutely necessary to get new rental housing built in our City and that this justifies the enormous cost of the program. But new data and recent reports from policy experts show this is not true. In fact, the 421a exemption likely has been making new housing development more difficult all along by inflating land prices.

This is pertinent since policy makers in Albany are currently considering whether to revive the program or not.

The 421a exemption costs City taxpayers over $1 billion a year, making it the most costly tax exemption in NYC. In 2014, the program subsidized over 152,400 residential units, but only 12,700 of those units were affordable while the rest were luxury or market rate. $100 was given away to subsidize luxury development for every $11 in actual benefit to the public.

This is why the real estate lobby, REBNY, fights so hard for the 421a program. Taxpayers have put up with the increasingly expensive and inefficient exemption for decades because REBNY’s influence made it seem inevitable. But, on January 1st, 2016, the program was suspended because of a surprising political impasse in Albany that triggered a sunset clause in the legislation.

Housing experts have long wondered exactly what impact the massive exemption had on the real estate market, but the tax exemption had been around for so long that we had no control-group data. Now, we can look at 2016 and see what actually happened.

To defend the program, REBNY has asserted unequivocally that “it was not feasible to build rental housing in New York City without the 421a subsidies,” and without it, new development would languish in many neighborhoods of the City.

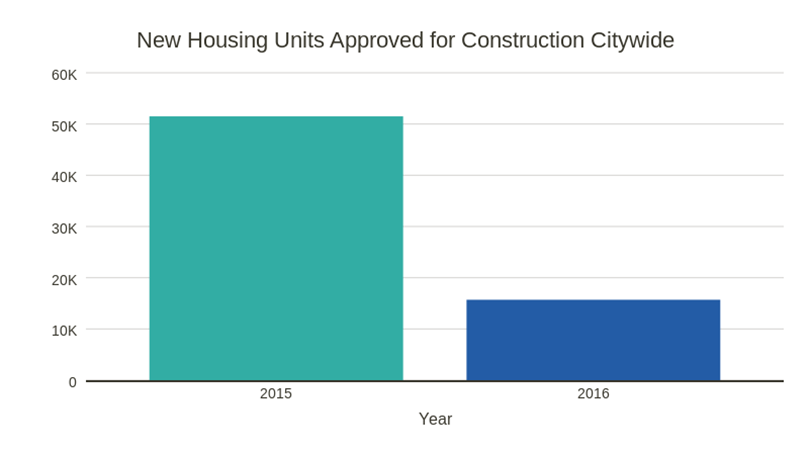

REBNY has pointed to data like this as proof that new housing development plummeted when the 421a exemption was suspended:

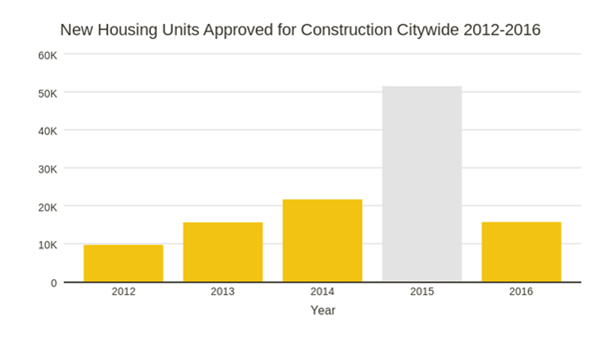

But, by focusing on those two years alone, REBNY is ignoring the larger truth. If you pullback a few years, the data shows something very different:

New building permits did drop in 2016, but that’s because 2015 was a unique year as developers rushed to file their permits before 421a came up for renewal and renegotiation in Albany in June of that year. This drove the volume of residential permit applications through the roof in 2015 as reported in the Wall Street Journal. But 2012, 2013, and 2014 – which were strong but more normal years for real-estate development – are almost exactly in line with 2016. There was an average of 15,654 new units approved from 2012 to 2014, and there were 15,697 new housing units approved in 2016. So, new housing development in 2016 occurred at normal rates, even in the absence of 421a.

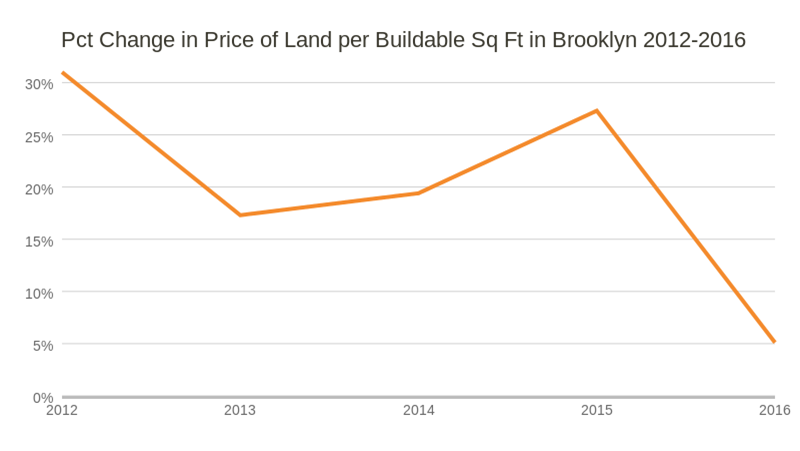

This data clearly contradicts REBNY’s claims and the expectation of many other housing policy experts, even those skeptical of REBNY, that development would drop off without the 421a exemption. And this instead sheds light on an important fact which has become clear in the past year – the 421a exemption may have been hindering new development in many neighborhoods by driving up land prices. In the past 12 months, new data has shown that the long-term presence of the inefficient 421a exemption inflated land prices. 421a acted as an artificial stimulant that drove up land prices, which is a major factor in whether a new development is economically feasible or not. Here we can closely examine the price of land in Brooklyn per buildable square foot (PBSF):

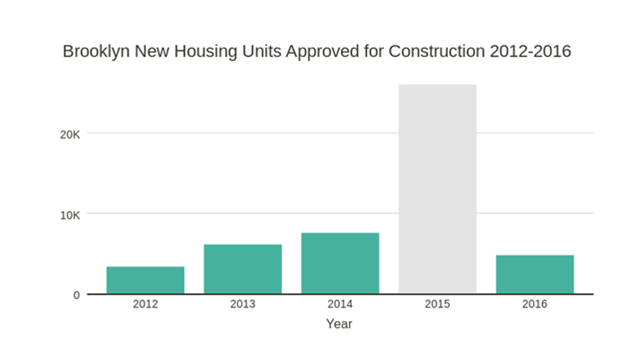

When we also take a closer look at the rate of new development in Brooklyn:

The price of land per buildable square foot in Brooklyn trends steadily upward from 2012 to 2015, averaging a 23.75% increase per year. Then in 2016, it suddenly levels off to only a 5% increase when 421a is suspended. This flattening of land prices is a significant part of the reason why new development in Brooklyn kept up a normal pace in 2016, even without the subsidy of the tax exemption. There were an average of 5,663 new units approved each year from 2012 to 2014 (excluding the unique rate in 2015), and there were 4,778 new housing units approved in 2016. The citywide numbers make up this very modest decrease with the overall increase in new units in other weak market outer borough areas. This effect of softening land prices is even more pronounced in the weaker outer borough real-estate markets. For example, in parts of the Bronx, lower land prices can be the margin of difference in whether development is feasible, or not, and where government policy should correctly encourage new development since those are the neighborhoods where it will be more naturally affordable. This answer isn’t entirely surprising. A report from the NYC Independent Budget Office last week stated that “because the 421a exemption is partially capitalized [economically inefficient], it contributes to higher land costs.”

What is most notable is how quickly land process adjusted down without the exemption, and how quickly development became more feasible and rose back to natural levels without it. Housing markets are complicated and 421a is just one factor that explains why new housing construction is still strong – there are numerous other factors, including the strengthening of rent levels in some weaker neighborhood markets. But the fact is, new private rental construction is happening without 421a across the City, and specifically in the crucial weaker market neighborhoods where REBNY asserted it would not happen. This unsupported assertion has been the centerpiece for REBNY’s argument that 421a must not only be revived, but expanded. It is important to note that, in 2016, New York City actually exceeded the affordable housing development goals set by Mayor de Blasio’s Housing New York Plan by building or preserving 21,963 affordable units, making 2016 the highest year on record for New York City affordable housing production. The fact that New York City did not need the 421a Exemption for its affordable housing targets is an indication that the 421a exemption is overwhelmingly a subsidy for high-end development. Furthermore, the City and State have better tax exemptions designed for affordable housing such as exemptions 420-c and Article XI.

We have long known that 421a is unjustifiably expensive and inefficient. Now we know it may not even accomplish the most minimum public purpose to justify its $1.4 billion price tag. Despite these facts, REBNY is currently working to convince the State legislature to make the subsidy even richer for themselves. (Even the New York Post condemned the new REBNY proposal in an editorial titled, Cuomo’s latest blow to city taxpayers). With the City and State facing the prospect of billions in additional local budget obligations because of the Trump federal budget cuts, legislators in Albany should resist the REBNY push to revive the 421a exemption.