The ANHD Blog raises the profile of our issues, and educates our member groups, city decision makers, and the general public on our core issue areas. The ANHD Blog offers sharp, timely and effective commentary on key public policy issues, as well as our work and the work of our member groups.

All of our blogs are sorted based on the issues, projects, special tags, and dates they are associated with, and you can use the dropdowns below to filter through our blogs based on these tags. Additionally, you can do a general search through our blog, using the search bar the right. If you can’t find what you are looking for, email comms@anhd.org.

How the City Can Fix the Bay Street Rezoning and Make Sure It Truly Serves the Community

Members of the Housing Dignity Coalition (HDC) turned out at the Staten Island Community Board 1 hearing last night to express their concerns over the proposed Bay Street rezoning that is now making its way through the 7-month public review process, or ULURP.

Speaking as faith leaders, congregants, and residents of Staten Island’s North Shore, these community members raised the vital question as to who this rezoning will ultimately benefit. It’s a question that must be addressed by the City before this rezoning can be approved, by ensuring broader and deeper affordability using all the tools at their disposal.

The bulk of the proposed rezoning would convert a 14-block stretch of Bay Street from manufacturing to residential zoning, at a range of permitted densities and heights spanning 5 to 14 stories. While this would create windfall profits for developers and landowners, its benefit for the average resident is less clear. Of the close to 1,600 new residential units the rezoning would allow on Bay Street, the City projects that 477 units would be “affordable” under Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH). But this projection assumes MIH Option 2, meaning that a family of 3 would have to earn $75,120 per year to qualify for the “affordable” unit.

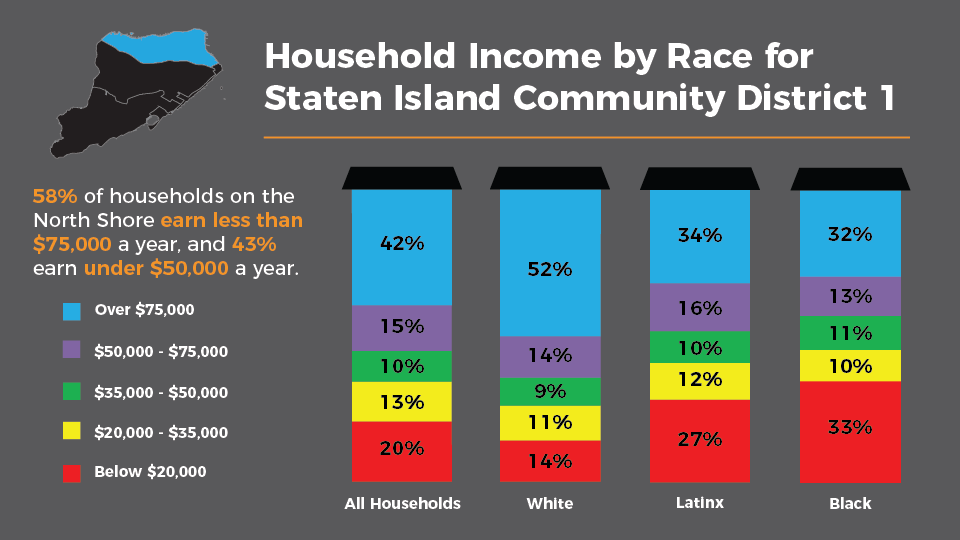

This matters because currently 58% of households on the North Shore earn less than $75,000 a year, while 43% earn under $50,000 a year. That means over half the households in the district won’t be served by this plan, with both the affordable and unregulated units out of their reach. These numbers are even more alarming when you consider race – 66% of Latinx households and 68% of Black households on the North Shore earn less than $75,000. These are the same households facing the highest rent burdens in the district – 70% of families earning less than $75,000 pay more than a third of their income towards rent, as opposed to just 3% of families earning more than $75,000 a year. These are the households that stand to gain the least, and lose the most, from this rezoning.

These numbers are especially concerning for an area like the North Shore where the vast majority of renters live in unregulated units without tenant protections. At the end of their current lease, most of these tenants can be displaced without cause. Unregulated tenants such as these are especially vulnerable to changing rental markets. The City itself acknowledges that the rezoning will bring in a higher income population than what currently exists around Bay Street. As the effects of this new population are felt, rents will almost surely rise putting these unregulated, low-income tenants at greater risk.

There are several steps that can and must be taken to remedy these problems. First is to ensure that only the deepest affordability options for MIH are made available as part of this rezoning. This means mapping only MIH Option 1 and Option 3 – which would set aside 20-25% of new units as affordable for families earning $37,000 to $56,000 on average. These are the families most in need and they are the ones who must be served.

Second is to ensure that public land is used for maximum public good. As part of this rezoning the City is taking steps to transfer four public disposition sites – city owned land – to private developers, including the large Stapleton Phase 3 site along the waterfront. Of the four city disposition sites listed, only two will require a percentage of income-restricted units at affordability rates left unmentioned; neither of these two will be 100% affordable. But public land is exactly the place where the City can achieve the deepest and broadest affordability; it is entirely in their control what gets developed on these sites. If each site were developed as 100% affordable housing, it could mean 443 more affordable units than under the current proposal.

Lastly, the City must do more to fight the displacement this rezoning may bring, including heeding the coalition's call for a mitigation plan for displaced tenants with both relocation services and fiscal support to help pay for increased renter costs.

Taken together, these changes could help ensure a rezoning that creates close to 50% affordable housing at levels that serve those households most in need, while creating a safety net for the numerous tenants who will be threatened by the rising rents this rezoning will bring. There is still time to make this a just rezoning, but the City must heed the call of the Housing Dignity Coalition and act now