New York’s Pandemic Rent Crisis

Almost two years into the pandemic, New York State renters and small and nonprofit landlords remain in dire crisis. ANHD’s new analysis of Census and housing court data reveals the extent of the severe rent debt and eviction crises and disproportionate impacts on people of color, which require both immediate and long-term solutions.

Executive Summary

Findings

Almost two years into the pandemic, New York State renters and small and nonprofit landlords remain in dire crisis. In a new analysis of Census and housing court data, ANHD found that:

- As many as 595,000 households remain behind on rent.

- Landlords have filed over 110,000 eviction cases during the pandemic.

- Rent debt and risk of eviction impact New Yorkers of color at dramatically higher rates.

- Mission-driven housing providers face revenue gaps that endanger their ability to house the lowest-income New Yorkers.

Recommendations

The ongoing rent debt and evictions crisis, which impacts communities of color at starkly higher rates than white communities, requires both immediate intervention and forward-thinking, comprehensive policy solutions. ANHD recommends:

Rent relief:

-

New York State should pursue all available opportunities for additional emergency relief funding, at both the Federal and State level.

-

New York State should focus resources on proactive outreach to communities most at risk of eviction and disconnected from digital services, particularly communities of color, immigrant communities, and seniors.

-

New York State should prioritize relief to housing providers who need it most: small and nonprofit landlords.

-

New York State should enact long-term funding streams for New Yorkers facing homelessness, such as the Housing Access Voucher Program (S2804B/A3701).

Eviction protection:

-

New York State should enact statewide right to counsel, ensuring all tenants facing eviction the right to an attorney (S6678A/A7570A).

Stability for tenants and long-term supply of permanently, deeply affordable housing:

-

New York State should enact good cause eviction protections so that tenants who pay their rent can maintain stability in their homes (S3082/A5573).

-

New York State should center deep, permanent affordability in its Five-Year Housing Capital Plan and require the creation of a comprehensive affordable housing capital plan every five years (S2193/A3807).

-

New York State should eliminate the 421a tax break and redirect resources to deep affordability, ending homelessness, and investing in public housing.

-

New York State should preserve affordability by giving tenants the opportunity of first purchase of buildings that are offered for sale (Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act, S3157/A5971) along with providing adequate funding for acquisitions and capital repairs.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is an unprecedented public health disaster and economic crisis, which is intricately tied to both housing security and long-standing, entrenched racial inequity. Despite billions of dollars of rent relief and a series of orders and regulations to stem evictions, tenants remain in acute crisis nearly two years into the pandemic.

The most recent round of stimulus checks was distributed in Spring of 2021 and extended pandemic unemployment expired on September 5, 2021, yet staggering numbers of New Yorkers remain out of work. As of mid-January 2922, approximately 811,000 New Yorkers – 11.9% of all of those not working – were caring for someone sick with COVID-19 or sick themselves. Another 7.1% of unemployed New Yorkers, 485,000 people, remain unemployed because they were laid off or their employer closed due to the pandemic. [1] Enduring unemployment due to sickness, caregiving needs, and business closures have resulted in ongoing rent debt for hundreds of thousands of households.

The housing and economic fallout from COVID-19 is fundamentally an issue of racial justice. As with hospitalizations and deaths from the virus, people of color have faced unemployment [2] and housing insecurity at dramatically higher rates than white New Yorkers. The following analysis highlights the profound disparities in housing security during the COVID-19 pandemic.

[1] Census Household Pulse Survey Week 41 Employment Table 3, New York State.

[2] https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/07/nyregion/bronx-unemployment-covid.html

Findings

1. As Many as 595,000 Households Remain Behind on Rent.

New York’s Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP), funded with over $2 billion in available rent relief, opened in June 2021. After taking office in late August, Governor Kathy Hochul was responsible for greatly accelerating the pace of approving applications for ERAP. Between the program opening on June 1 and August 23, a day before Governor Hochul took office, New York State had paid out $203 million in rent relief. [3] As of November 19, the State had paid out $1.05 billion and approved $1.03 billion more, exhausting the program funds. [4] The State closed the ERAP application portal to almost all New Yorkers on November 14, and reported that 296,511 total applications had been submitted as of January 18, 2022. Of those applications, 108,242 payments were made and another 52,889 applications were approved pending landlord verification, totalling 161,131 applications paid or approved. [5]

On January 27, 2022, Governor Hochul announced New York State requested an additional $1.6 billion from the Federal government, which the State claims could serve 174,000 households. However, ANHD’s analysis of the most recent Census Household Pulse Survey Data showed that as of January 10, 2022, 17.2% of respondents in New York were behind on rent payments, translating to 595,000 of the State’s 3,461,000 renter households. [6] This means that the number of households behind on rent in mid-January was almost four times the number of households that have received or been approved for relief and almost twice the number of households who would be served even if New York were to be granted the requested $1.6 billion.

Additional funding of $1.6 billion would offer significant relief to households that have already applied to the program, but our analysis indicates there may be hundreds of thousands of households it would not reach. Ongoing rent debt remains a severe problem that requires immediate intervention, as well as sustained attention and prioritization for the duration of the pandemic and beyond.

2. Landlords Have Filed Over 110,000 Eviction Cases During the Pandemic.

Throughout the pandemic, New York State has issued an amalgamation of orders and regulations that have offered tenants varying levels of protection against eviction at different times. Among these are:

- The Tenant Safe Harbor Act, which prevents eviction for rent owed during the pandemic, but allows landlords to collect money judgments – which could result in tenants owing tens of thousands of dollars in back rent.

- The COVID-19 Emergency Eviction and Foreclosure Prevention Act (CEEFPA), which allowed tenants to sign a hardship declaration asserting that they were financially impacted by COVID-19 and unable to pay their rent, which would stop their eviction case from proceeding.

- ERAP, which stops an eviction case from proceeding while an application is being processed and protects tenants from eviction for nonpayment of rent during the period for which they were granted relief.

New York State’s closure of the ERAP portal to most New Yorkers in November 2021 cut off tenants who had not yet applied from the eviction protections it offered. Following a lawsuit brought by the Legal Aid Society, New York State was subsequently compelled to reopen the ERAP Portal on January 11, 2022. This has returned a layer of protection to tenants, but the situation remains confusing and disorienting. Furthermore, ERAP-based eviction protection depends on the portal remaining open, which is subject to legal action and not guaranteed. On January 15 2022, CEEFPA expired. CEEFPA was an important source of stability and protection against eviction for tenants who have not been able to keep up with their rent, and its expiration was a blow to tenants who have experienced severe uncertainty about their ability to stay in their homes. Despite the layers of eviction protections in place, landlords were able to file tens of thousands of eviction cases during the pandemic, subjecting those tenants to eviction as soon as various protections expire. Based on data from the New York State Office of Court Administration, we estimate that landlords filed over 110,000 residential eviction cases in New York State during the pandemic, 75,500 of which are still active. For now, applying to ERAP allows tenants protection from eviction while the case is under review–however, without additional funding to address enormous remaining rent debts, a pause is only a temporary solution.

- The Tenant Safe Harbor Act, which prevents eviction for rent owed during the pandemic, but allows landlords to collect money judgments – which could result in tenants owing tens of thousands of dollars in back rent.

- The COVID-19 Emergency Eviction and Foreclosure Prevention Act (CEEFPA), which allowed tenants to sign a hardship declaration asserting that they were financially impacted by COVID-19 and unable to pay their rent, which would stop their eviction case from proceeding.

- ERAP, which stops an eviction case from proceeding while an application is being processed and protects tenants from eviction for nonpayment of rent during the period for which they were granted relief.

New York State’s closure of the ERAP portal to most New Yorkers in November 2021 cut off tenants who had not yet applied from the eviction protections it offered. Following a lawsuit brought by the Legal Aid Society, New York State was subsequently compelled to reopen the ERAP Portal on January 11, 2022. This has returned a layer of protection to tenants, but the situation remains confusing and disorienting. Furthermore, ERAP-based eviction protection depends on the portal remaining open, which is subject to legal action and not guaranteed..

On January 15, 2022, CEEFPA expired. CEEFPA was an important source of stability and protection against eviction for tenants who have not been able to keep up with their rent, and its expiration was a blow to tenants who have experienced severe uncertainty about their ability to stay in their homes.

Despite the layers of eviction protections in place, landlords were able to file tens of thousands of eviction cases during the pandemic, subjecting those tenants to eviction as soon as various protections expire. Based on data from the New York State Office of Court Administration, we estimate that landlords filed over 110,000 residential eviction cases in New York State during the pandemic, 75,500 of which are still active. [7]

For now, applying to ERAP allows tenants protection from eviction while the case is under review–however, without additional funding to address enormous remaining rent debts in New York, this pause is only a temporary solution.

3. Rent Debt And Risk Of Eviction Impact New Yorkers Of Color At Dramatically Higher Rates.

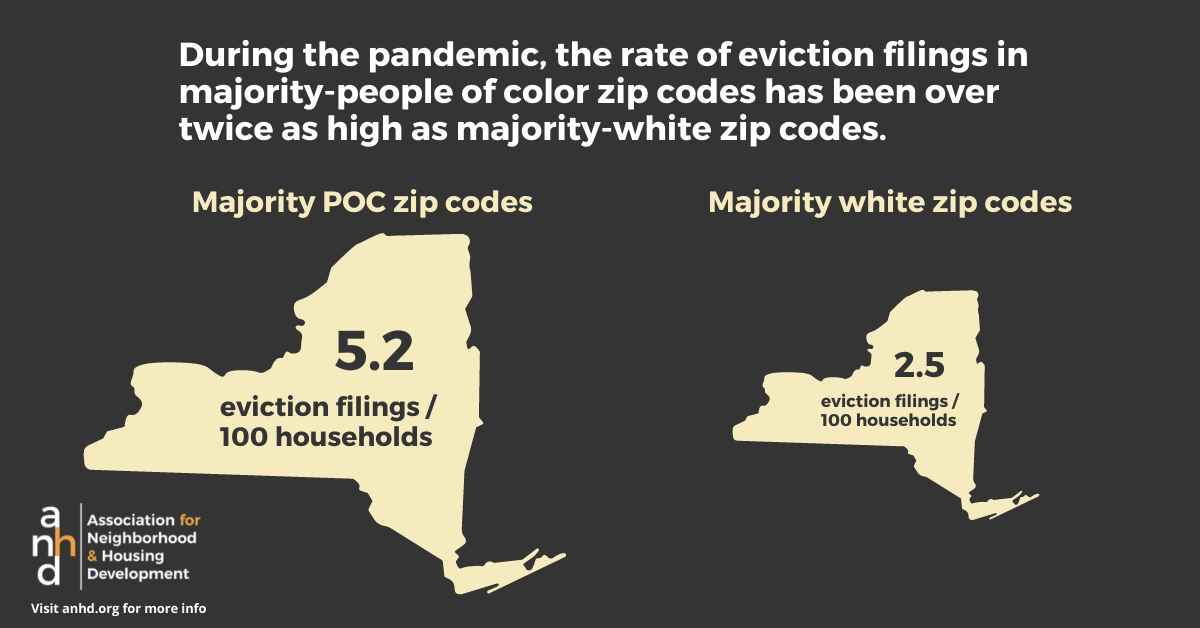

During the pandemic, the rate of eviction filings in majority-people of color zip codes across New York State has been over twice as high as majority-white zip codes. [8] In zip codes where over 50% of residents are people of color, the number of eviction filings from March 23, 2020 through January 7, 2022 was 5.2 per 100 renter households. In zip codes where over 50% of residents are white, the rate was 2.5. This finding parallels trends ANHD found in March 2021, that eviction rates in zip codes with the highest rates of COVID death, also predominantly communities of color, had an eviction filing rate almost four times as high as neighborhoods hit least hard by COVID. [9]

The trend is clear when homing in on New York City. All but one majority-white zip code, 10018 in West-Midtown, had a rate of fewer than five eviction filings per 100 renter households. On the other hand, over one-third of majority-people of color zip codes (36 out of 97) had an eviction filing rate over five per 100 households. Five majority-POC zip codes had eviction rates over nine per 100 households, in northwest Staten Island (10303), Corona in Queens (11368), and three zip codes concentrated in the South Bronx and Kingsbridge Heights/Fordham neighborhoods, a clear hotspot (10468, 10457, and 10452).

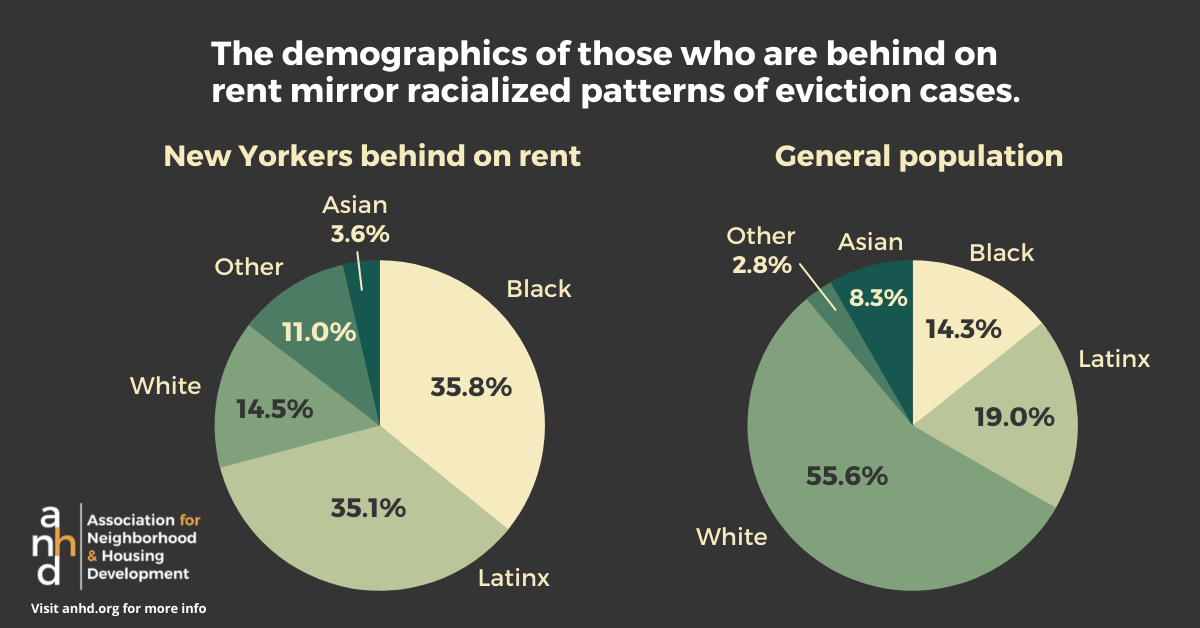

The demographics of those who are currently behind on rent mirror the racialized patterns of eviction cases, and the racial and ethnic disparities are alarming. Of all New Yorkers who are behind on rent, 35.8% are Black, two and a half times the share of the general population (14.3%). Hispanic and Latinx New Yorkers make up 35.1% of those who are behind on rent, versus 19.0% of the general population. And white New Yorkers make up only 14.5% of those who are behind on rent, which is less than one third of their share of the general population (55.6%). Combined, people of color constitute 85.5% of New Yorkers who are behind on their rent, but just 44.4% of the general population. [10] The over-representation of people of color among New York households that are currently behind on rent, almost half their share of the general population, is staggering.

4. Mission-driven Housing Providers Face Revenue Gaps That Endanger Their Ability To House The Lowest-income New Yorkers.

A survey of ANHD’s membership revealed that nonprofit, mission-driven housing providers continue to have severe gaps in rental income that hinder their ability to safely house New York’s lowest-income tenants. Surveyed nonprofit housing providers submitted between 15 and 340 ERAP applications ranging from $96,154 to $2,289, 428 in back rent. On the whole, those housing providers have been approved for less than half of their applications, leaving them with a gap of between $62,558 to $810,123 in unfunded relief. On average, surveyed organizations had unapproved applications totalling $339,374, or $5,078 per unapproved application.

A revenue gap of hundreds of thousands of dollars is staggering for a community-based housing provider with extremely limited resources. Not only is rental income needed for nonprofits to maintain their buildings and pay staff, it also supports the provision of essential social services in the community.

Furthermore, this data only represents applications for rental arrears from March 2020 to November 2021. ANHD’s nonprofit housing provider members have echoed that the unemployment crisis is ongoing, tenants are still falling behind in rent, and the first round of ERAP funding was inadequate. One ANHD member said, “there is still a tremendous balance of folks in need who we did not submit for various reasons and would have if there was additional funding and an extension of time.” Nonprofit housing providers also faced significant challenges in submitting applications due to limited staff capacity, which put them at a disadvantage compared to large and corporate landlords. As one member said, “by the time we finally had a good system going, the program was over.”

Nonprofit landlords face similar challenges as small landlords, who lack the cash flow to cover large revenue gaps during the pandemic. They continue to need urgent assistance; rent relief so far has been simply inadequate to meet the need. There is a need for longer term solutions to address rental arrears for low-income households and to keep the mission driven organizations serving these households afloat.

[3] NYS Office of Temporary and Disability Assistance (OTDA), New York State Emergency Rental Assistance Program Rent Arrears and Prospective Rent Payments by Jurisdiction Through August 23, 2021. Note: reports and summary figures are regularly updated and no longer visible on the OTDA website for earlier dates. ANHD downloaded and tracked ERAP reporting data on a regular basis throughout program implementation.

[4] NYS OTDA ERAP Reports, Summary through November 19, 2021.

[5] Ibid, Summary through January 18, 2022.

[6] Census Household Pulse Survey Week 41 Household Table 1b, New York State; Census American Community Survey (ACS) 2019 5-Year Estimates, B25003 (Tenure). 17.2% of respondents reported being behind on rent. That figure multiplied by the total universe of renter households in NYS, 3,461,296, equals an estimate of households behind on rent of 596,813.

[7] Data from the New York State Office of Court Administration (OCA) via the Housing Data Coalition in collaboration with the Right to Counsel Coalition. This figure includes New York State cities and does not include towns and villages that do not report case data to OCA, so it is an underestimate. Total number of non-payment and holdover eviction filings and total filings with an active status in New York State between March 23, 2020 and January 24, 2022. Based on available property type data, ANHD estimates that approximately 5.13% of statewide eviction cases are commercial rather than residential, which is accounted for in these estimates: 116,794 total cases adjusted to 110,802 estimated residential cases and 79,587 active cases adjusted to 75,504 estimated active residential cases.

[8] Ibid; ACS 2019 5-Year Estimates, B25003 (Tenure) and B02001 (Race). Non-payment and holdover eviction filings March 23, 2020 through January 7, 2022 divided by number of renter households in majority-people of color zip codes versus majority-white zip codes.

[9] https://anhd.org/blog/220000-tenants-brink-and-counting, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/17/realestate/new-york-city-renters-evictions.html

[10] Census Household Pulse Survey Week 41 Household Table 1b, New York State, Census American Community Survey (ACS) 2019 5-Year Estimates, A03001 (Race), A04001 (Hispanic or Latino by Race).

Recommendations

New York State needs both emergency and long-term solutions that meet the scale of the need and address our housing and homelessness crisis in its entirety.

The temporary protection from eviction that applying to ERAP offers while the application is pending is a critical lifeline to tenants, and the application portal should stay open to tenants. However, it is not sustainable without additional relief to address the immense remaining rent debt, especially for small and nonprofit landlords without the cash reserves to cover revenue gaps.

- New York State should pursue all available opportunities for additional emergency relief funding, at both the Federal and State level.

- New York State should focus resources on proactive outreach to communities most at risk of eviction and disconnected from digital services, particularly communities of color, immigrant communities, and seniors.

- New York State should prioritize relief to housing providers who need it most: small and nonprofit landlords.

- New York State should enact long-term funding streams for New Yorkers facing homelessness, such as the Housing Access Voucher Program (S2804B/A3701).

Thousands of evictions have moved forward during the pandemic and continue to do so. Eviction cases threaten communities of color at dramatically higher rates than predominantly white communities. All tenants facing eviction deserve representation for a fair process.

- New York State should enact statewide right to counsel ensuring all tenants facing eviction the right to an attorney (S6678A/A7570A).

New York State needs long-term solutions to guarantee tenant rights to safely remain in their homes and sufficient supplies of permanently and deeply affordable housing that meets the scale of the need.

- New York State should enact good cause eviction protections so that tenants who pay their rent can maintain stability in their homes (S3082/A5573).

- New York State should center deep, permanent affordability in its Five-Year Housing Capital Plan and require the creation of a comprehensive affordable housing capital plan every five years (S2193/A3807).

- New York State should eliminate the 421a tax break and redirect resources to deep affordability, ending homelessness, and investing in public housing.

- New York State should preserve affordability by giving tenants the opportunity of first purchase of buildings that are offered for sale (Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act, S3157/A5971) along with providing adequate funding for acquisitions and capital repairs.